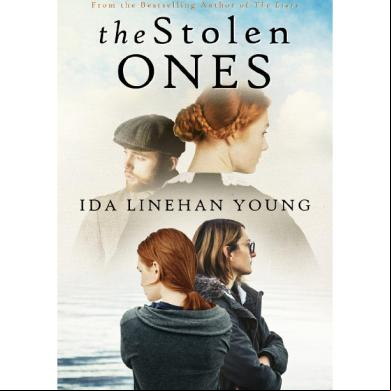

The Stolen Ones 5h1q1t

This document was ed by and they confirmed that they have the permission to share it. If you are author or own the copyright of this book, please report to us by using this report form. Report 3i3n4

Overview 26281t

& View The Stolen Ones as PDF for free.

More details 6y5l6z

- Words: 81,281

- Pages: 307

- Publisher: Flanker Press

- Released Date: 2021-07-20

- Author: Ida Linehan Young

Contents

Praise for Being Mary Ro The Stolen Ones Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Dedication 1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

Historical Notes About the Author

Praise for Being Mary Ro

“A charming book.” the sudbury star

“I cannot imagine anyone not enjoying Being Mary Ro. The material is suitable for mature young readers, contains small sketches (by Melissa Ashley Cromarty), and is an excellent first novel for Ms. Linehan Young.” — The Miramichi Reader

“We’re only halfway through the novel when Mary pulls the trigger. The strength and courage required to shoot the pistol is the same strength and courage that afterwards allows Mary to travel to . . . and pursue an independent career as a . . . I’m not telling. Find out for yourself. Read Being Mary Ro. It’s first-rate entertainment.” — The Telegram

Praise for The Promise

“A well-written story that many will want to read in one night . . . just because the plot is that good.” — Edwards Book Club

“Ida Linehan Young . . . evokes a time and a place and a strong female lead. She has also well-positioned this book to pilot into a follow-up. Her knowledge of, and research into, the processes pre-20th century household labour, or the state

of the justice system after the 1892 fire, pay off.” — The Telegram

Praise for The Liars

“Ida Linehan Young does well-researched well-paced melodrama well.” — The Telegram

“There is no doubt that she is amongst the best of the best of Newfoundland’s storytellers. . . . If you like good historical fiction stories told in a similar vein to Genevieve Graham’s, then you’ll enjoy this trilogy of turn-of-the-last-century novels from the prolific pen of Ida Linehan Young.” — The Miramichi Reader

“The storyline of mystery, intrigue, and plot twists that Linehan Young expertly crafts in The Liars is the result of true events that occurred in the late 1800s in Newfoundland. Her ability to formulate a fictitious story by intertwining the results of her research with that of the plot details conceived in her mind is brilliant. The Liars is another compelling read for those who enjoy history, suspense, and wonderfully descriptive writing. The female characters are strong, simple, but complex individuals, who reinforce the theme that there is no greater warrior than a mother protecting her child. Kudos to Ida Linehan Young in creating a work of art that will leave you wanting more.” — Fireside Collections

“Ida Linehan Young skilfully weaves this complicated tapestry from its first warp and woof on a loom in Labrador to its final hemstitch in North Harbour, St. Mary’s Bay.” — Harold Walters, Life on this Planet

The Stolen Ones

Ida Linehan Young

Flanker Press Limited St. John’s

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Title: The stolen ones / Ida Linehan Young. Names: Linehan Young, Ida, 1964- author. Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20210226188 | Canadiana (ebook) 20210226196 | ISBN 9781774570623 (softcover) | ISBN 9781774570630 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781774570647 (PDF) Classification: LCC PS8623.I54 S76 2021 | DDC C813/.6—dc23

—————————————————————————————————————— -----——

© 2021 by Ida Linehan Young

all rights reserved. No part of the work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic or mechanical—without the written permission of the publisher. Any request for photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems of any part of this book shall be directed to Access Copyright, The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 800, Toronto, ON M5E 1E5. This applies to classroom use as well.

Printed in Canada

Cover Design by Graham Blair

Flanker Press Ltd. PO Box 2522, Station C St. John’s, NL Canada

Telephone: (709) 739-4477 Fax: (709) 739-4420 Toll-free: 1-866-739-4420

www.flankerpress.com

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

We acknowledge the financial of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) and the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Department of Tourism, Culture, Industry and Innovation for our publishing activities. We acknowledge the of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $157 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country. Nous remercions le Conseil des arts du Canada de son soutien. L’an dernier, le Conseil a investi 157 millions de dollars pour mettre de l’art dans la vie des Canadiennes et des Canadiens de tout le pays.

Dedication

With fondest memories of my cousins Brenda and Pat Critch. They will always be ed with an abundance of love. In Memory of Elsie Ryan, who died from burns in North Harbour two days after her nightdress caught fire, February 23, 1920. She was ten years old. For my grandparents, Frank and Ida Power, and Edward and Mary Theresa (Nash) Linehan, whose lives inspire me with a curiosity for the past. As always and forever for my father, Edward Linehan, my sister, Sharon, and my brothers, Francis, Richard, Harold, and Barry Linehan. You were all loved beyond measure.

1

Boston April 2020

“I can get her, Mom,” Tiffany Carter said softly, her shaky voice betraying her attempt to be strong. “No, it has to be me. They’re strict about that. You stay here,” Darlene said woodenly as she girded her will to be up to the task. “Please be careful.” Tiffany swallowed a gasp and grabbed her mother’s arm frantically. “I’m scared.” “I won’t be long.” Darlene’s voice was a hushed whisper. She gulped for air to quell the mounting anxiety from gaining ground. Darlene stepped out of the taxi and into a nightmare. Who was she kidding? This was day seven, or eight, or ten, or fourteen of the pandemic, and normal was no more. The streets were eerily quiet for downtown Boston on a Tuesday. She glanced back and saw Tiffany lean forward and stare wide-eyed after her through the lightly tinted glass. Darlene turned and ed the line that had formed with its terminus, the side door of the huge brick building. The silent and sombre procession was slow. It was as if an invisible turnstile controlled everything. As one person clicked out of the alley, she clicked forward toward the entryway and somebody like her ed the other end of the line. They shuffled forward, mindful of the worn painted lines, directional arrows, scuffed footprints, and warning signs on the dirty concrete. Counting time seemed a distant memory of a period when there was never

enough of it. Like when she had rushed to work after being waylaid by something that was now insignificant, or when she’d caught a bus with Tiffany after a shift at the diner, or when the laundry had finished washing and she needed to find a free dryer so that the task wouldn’t take all evening. The list had been endless in the feverish pace of her daily life. Now, putting one foot in front of the other was the only way she could survive, and time just sat there waiting to start once again. Shuffle after shuffle, orderly, quietly, they moved until she was second in line. The man ahead of her said a name, then bowed his head as the door closed and the attendant vanished. Her heart pounded, and she didn’t know if she would be able to speak when she needed to form words. The person returned and handed the man ahead of her a small package. He raised it to his face, wiped his eyes with the cuff of his coat, turned, and left without making eye . The door slammed. It was loud, like a cannon had been fired in the alley, the noise ricocheting all around her. Darlene moved up, her wobbly legs barely keeping her upright with each step. She closed her eyes at the yellow sign emblazoned with bold black letters that read Employees only beyond this point. She opened them when she heard the click of the latch release on the other side of the steel barrier. “Name, please,” the masked man dressed in the washed-out paleness of blue paper clothing said, his weary eyes staring at the wall over her head and reflecting distorted defeatedness on the visor that covered them. “Em-Emma Carter,” she stammered. “Pardon? Please speak up.” Darlene cleared her throat, pinched her mask, and pulled it away from her mouth. “Emma Carter.” The door closed with a whoosh and resounding clunk. She hung her head. How was she going to do this? How was she going to go on? “Ma’am. Emma Carter.” Darlene shook her head to clear the fog and gazed up at the man two steps above

her and holding the grey door back with his hip. “Your name?” “Darlene Carter.” “Do you have your identification?” Darlene nodded and pulled her driver’s licence from her coat pocket and raised it for him to see. He bent forward, nodded, pulled away, and straightened. He made notes on the clipboard and rested it on the ledge of the stairwell inside the door. His latex-covered hands grabbed the metal cylinder that was also resting on the ledge. He finger-checked a number on it against something on the form, pulled off a tag, and turned to her. His voice and movements were robotic as he reached forward and said, “Please don’t touch me.” Darlene nodded and cupped her hands together, pushing them forward as the person ahead of her had done. The man plopped the small cylinder into her palms. She braced for the mighty weight that would be far from physical. The door whooshed closed. She stood, dazed, with her arms outstretched and stared into nothingness. The person behind her ahemmed, bringing her back from wherever she’d gone, and she staggered away from the door and out of the alley. The trudge toward the street was in slow motion. Before she realized it, she was in the sunshine of the sidewalk. Her arms and heart ached in unison. The taxi door slammed. “Mom!” Tiffany’s shout echoed off the buildings, and the pigeons on the marble step at the front entrance took flight. Several heads rose momentarily in a lineup that extended down the block. Darlene looked away from the cool metallic container resting in her open palms as Tiffany reached her. Tiffany whipped a bottle of sanitizer from her purse and

smothered Darlene’s hands as well as the urn. She guided her mother to the cab, opened the rear door, and let her in. She pushed Darlene to the middle and bundled in beside her. Tiffany held her mother, and they both wept as the taxi pulled away from the curb. Emma Carter became a memory, reducing them to a broken and sad family of two. Darlene took on the weight of duty her mother had carried as head of the household. Every ounce of Darlene’s being dislocated and began the process of settling back into a crippled form that would remain uneven and, according to the phone call from the psychologist that came a month later, someday tolerable.

2

John’s Pond, Newfoundland 1878

Mary Rourke splayed her fingers and brushed them along the furry tips of the tall hay growing at the edge of the path. The hem of Mary’s skirt swayed to the rhythm of her walk, darting from side to side as if it, too, had a purpose. Her red hair caught fire as she ed through shafts of sunlight streaming between the limbs of the spruce trees above the old slide path. The trail was beaten down in the winter by the horses and sleds hauling firewood out from the country to the little fishing village of John’s Pond, nestled on the coast of St. Mary’s Bay. In the summer, the trail was a ageway to their secret hideaway, a tiny jut of land on the bend of the brook where a pond formed. It was a quiet place, where silence was broken by the sound of the trout breaching the glassy surface, lured by the insect that ventured too close, or by the hum of the bumblebee in the dandelion at the edge of the thicket, or by the sound of Mary turning a page. Their first meeting there had been an accident of sorts. Mary’s father had sent him to find her. She’d gone for a walk earlier in the day and hadn’t returned for supper. Peter Nolan had set out along the trail and nearly jumped out of his skin when she spoke from the shelter of the trees as she was stepping out onto the path. They both laughed, both startled by the encounter. Mary had a book in her hand, and she said she’d been distracted by the story and forgot the time. A few days later, he had been collecting eggs, one of the many tasks Mary’s father put to him, finding the nests of the hens that were laying out. Mostly he

wanted to keep busy so he wouldn’t feel the sting of the leather strap from his Aunt Johannah. Peter liked and respected Mary’s father. He’d enjoyed spending time with the Rourke family. Menial chores like finding eggs or bringing in water hadn’t bother him. Mr. Rourke paid Peter a pittance once a month for cutting wood, which the man was quite capable of doing on his own. Peter protested with a bit more vigour than he felt—in truth he was saving every coin he could get to leave John’s Pond behind. However, because of Mr. Rourke’s intervention with Aunt Johannah, things had gotten markedly better at home, and leaving wasn’t a certainty like it used to be. That day, he fooled himself into believing he wasn’t overtaken with curiosity and hadn’t really wanted to see what Mary was up to. He was looking for eggs. When he pushed through the thick young spruce along the side of the path, he noticed her within moments, surrounded by dandelion and daisies, sitting, leaning against the thick trunk of a large tree, and reading a book. The sun, glistening off the pond in the background, glowed around her. He cupped his hand over his eyes to break the glare until her dark shape came into focus. He drew a deep breath that he smothered with his hand so she wouldn’t know he was there. That had been the first time his normal teasing, roughhousing response didn’t kick in. Instead, his stomach went all aflutter, and frightened by this new sensation, he backed out of the scene and ran to Rourke’s, dropped off the eggs he’d found, and headed to Aunt Johannah’s. He believed he’d come down with a sickness that might be cured at the end of Aunt Johannah’s leather belt. The lure of the newness of this strange illness pulled him back. She sat quietly by the tree. His body tensed around his bones, and a wave of heat flooded through him. That time he forced himself to stay and watch her from the cover of the spruce. She was so mesmerizing and his turmoil so unfamiliar, he dozed off and landed head first in the bushes. He crawled out to the trail to the sound of a muffled giggle and ran home. The third time he ventured there, she stirred, her ear twitched, and she turned toward him. Mary asked him what he was looking at. She asked him to her and patted the ground at the base of the tree. A surge of fear stampeded through him. He ran home again, forgetting to drop off the eggs on his way. It was almost two weeks before Peter dared go there again. This time, Mary had

an extra book with her. She told him she’d carried it for him for a week. This time, he suppressed the urge to run and gathered the courage to approach her. He sat silently on a large grey stone a little way into the clearing and threw rocks into the pond while she read. He didn’t take the book she’d offered and concentrated instead on the plop of the rocks as they were swallowed by the pond. It was a few weeks later before he dared to get closer. He built a bough house there that year, just to be around her. In the winter, she read in the house or in the hay on the stable loft after school. He found many reasons to help Mr. Rourke that winter. The next summer, when she returned to the woods, he busied himself with chores, getting up early to get them done, before heading to where Mary was. He was fifteen and didn’t tire of listening to her talk about her dreams. He even had illusions of perhaps having some of his own. She wanted to be a nurse like her mother. He didn’t want to be anything other than with her. When he was sixteen, the romance finally blossomed into a first kiss. It was awkward and startling and beautiful. By the time he was seventeen, Peter was certain he wanted to marry her. There would be nobody else in the world for him but her. His brother Ed wanted him to go off to sea, perhaps to Boston to make their fortune. The time was right. Aunt Johannah had ed away a few months earlier, severing the tenuous familial connection to John’s Pond. He couldn’t wed Mary for at least two more years and not without something to offer. Peter wanted her father to know he’d be a good man to his daughter, just like her father had taught him. He had to be a provider. He couldn’t do that with the little work he’d gotten in the cannery the past two summers. He struggled with the want to stay with her and the want to make something of himself for her. Peter hadn’t told Mary about Ed’s plans because he didn’t want her to be upset. Today, when he watched her come up the path, his heart was pounding as he ran to the tree to wait for her. “Peter,” she called.

He waved and patted the ground next to him, his heart racing as if he’d run up along the ridge and back. She bounded toward him, fell to her knees, and cuddled in beside him. “What’s that pout for?” he asked. “It’s just that it was such a wonderful day. School’s almost out. But Mom says I have to go to Mount Carmel in the fall to get more education if I’m going to be a nurse.” She nestled in closer. “I don’t want to go.” “I know how that feels,” Peter said wryly as he tightened his arm around her. “Are you going to Mount Carmel, too?” She pushed away from him. Her eyes widened with excitement and prospect as she gazed at him expectantly. Peter cupped her face with his hands. She knew he had only stayed around the last two years because of her and Ed. Most others his age were long fishing with their fathers. “No, farther than that. Me and Ed are going to St. John’s and then to Boston looking for work.” Mary pushed herself to her knees and stared at him. “What?” He repeated what he’d said. “But why?” He paused. Over Mary’s shoulder, Peter watched two sparrows as they flitted from one branch to another in the thick spruce on the other side of the pond. A chase as old as time and much less complicated. She touched his arm and drew his eyes to her face. He gently grazed her cheek with the back of his fingers before pushing a fallen lock of hair behind her ear. “I have nothing to offer you. I want to build a home, build a life, but I can’t do it if I stay here.” His voice held an air of regret. “There’s logging in Colinet, or you could go fishing.” “Ed is leaving. I have to go with him.” Peter looked away.

“You could stay.” “You know how Ed is. Always getting himself in trouble.” “And you’re always there to help him out.” “I’m all he has. It’s just the two of us.” He reached for her hands, but she stuffed them in the pockets of her dress. “I have no hold on you, Peter Nolan. No hold at all.” She stared at the ground as she forced the words from her mouth. “That’s not what I’m saying, Mary. I want to come back to you. In fact, I want to marry you. Will you wait for me?” Mary raised her head and searched his face. A slow smile came. She released her hands and grabbed his arms. “Peter, I’ll wait for you forever. You know that. I love you, too. I just don’t like the thought of not seeing you for who knows how long.” “I don’t have much to offer right now. But I have this.” Peter fished a braided line from his pocket. It formed a small and intricate loop. He took her hand and moved the line in on her finger. “Someday, my darling Mary, this will be a golden band.” He kissed her. “I’ll come back for you as soon as I can. You won’t have to wait for me forever.”

Two years later, he stood at her doorstep. She was a vision. He had to stop himself from sweeping her into his arms and running away from the world toward their hideaway, where he could unchain himself from the burden of his duty to Ed. She pulled on her coat, her eyes glistening and her face hopeful. Mary came to sit on the sawhorse beside him. She was aglow with love and promise. She reached for his hand, but he didn’t take it. He would be scarred forever by the look on her face when he told her that he was getting married the following week. “Her name is Martha Walker.”

He was hopeful that his upside-down world would someday be tolerable and the heartbreak he felt in that moment would stitch closed and see its way to mending. The scar, he was sure, would torment him forever.

3

Boston Present day, June 2021

Darlene pulled the zipper closed on her mother’s large violet-coloured suitcase. She had everything she needed for the trip, and what she didn’t have, she’d buy. Her heart wasn’t in it as Tiffany joked, “What does one wear when going to Newfoundland?” Neither of them had any idea what it was like there beyond the images they saw online. “Tiff, are you packing or are you gaming?” “Gaming? Do you even know what that is?” “I might,” Darlene said as she gave the zipper one final tug. “That stuff you look at on your phone.” Tiffany laughed. “You mean my social media?” “Whatever they call it.” “You must be the only person who’s not online.” “I have email.” Tiffany stopped in the hall and shook her head while she rolled her eyes. Her mother smiled at her. “And I’m packed, Mom. I was finished before you.” Tiffany, with her auburn ponytail wagging behind her, sauntered into the bedroom, flopped across the knitted throw at the foot of her mother’s double bed, spread her arms, and gazed at the ceiling with a sigh.

“So dramatic,” Darlene muttered under her breath. Tiffany rolled to her side, bent her elbow beneath her, and propped herself on her upturned palm. “I’m losing so many shifts down at Ray’s.” “Uh, uh, uh,” her mother said as she wagged her finger at Tiffany. “Ray’s will be there when we return. Despite what he says, he will take you back in a flash. You’re his best girl.” “He keeps me there because of you,” Tiffany said, her grin wide. She winked at her mother. “Ray Junior keeps asking about you.” “Ray Junior is full of himself. Don’t you give him my number.” Tiffany pulled her phone out of the back pocket of her faded jeans, and Darlene feigned a grab for it. Tiffany pulled away and laughed. “He’s not a bad guy, Mom. And he’s not hard on the eyes, according to the old women who eat there.” “Are you calling me old?” Darlene asked as she eyed her daughter. “Besides, you shouldn’t be worrying about work.” “I’m saving for college, ,” Tiffany said. “You’re nineteen, .” “What were you doing when you were nineteen?” “Probably working at Ray’s.” Darlene paused and smiled. “With Grandma. Oh, and Ray Senior, and probably trying to avoid Ray Junior.” Tiffany reached out and patted the suitcase. “Is Grandma in there?” She craned her neck to get a glimpse of the nightstand behind Darlene. “No,” Darlene said as she reached around and picked up the metal urn. “This was Grandma’s trip. She is going in my purse.” “Are you sure you’ll get through customs with her? I checked on the website. It

only mentioned requiring proof of vaccination, but it wasn’t clear to me that you could take, you know . . .” “I called, and the agent assured me that it would be all right. I’d feel bad stuffing her in this tightly packed thing.” “And your purse is better because . . . ?” Tiffany asked with a grin. Darlene threw a pillow at her and laid the urn back where she got it. “I’ll be putting her in my coat pocket when I stow my purse. I want to have her close to me. This was Grandma’s dream trip. She bought this purple luggage for it.” “Violet, Mom. She said violet was for mystery. And for the future.” “Future, right.” Darlene shook her head and closed her eyes. “It should be you and her going tomorrow.” She straightened from her task, threw her head back, and let out a heavy sigh. “It should have been you two going last year. Damn COVID.” Darlene squeezed her hands into fists by her side. Then she raised her fingers to her brow and massaged her temple. Her head hung low. “I still can’t believe she’s gone,” she whispered. She dabbed at her eyes with her sleeve after a sudden spill of tears. Tiffany rolled onto her belly and wrapped her arms around the pillow, resting her chin there and staring at her mother. “Grandma would be so proud that you’re bringing her to Newfoundland.” “I know, baby. I know. It’s hard sometimes, that’s all.” Darlene grabbed the portfolio from the bed, pulled out several sheets, and slid the rest into the front pouch of her carry-on. “It was just the three of us for so long. I miss her.” She grabbed her glasses from the nightstand and sat on the bed, her face sombre as her finger hovered and grazed along the handwritten words. “I miss her, too,” Tiffany said. A flicker of sadness shadowed her eyes, and her lips drooped momentarily to a frown as she regarded her mother. “This was Grandma’s mission to find a family.” She made a fist and thrust it Supermanstyle into the air, her voice a booming echo on the word,“family.” They both laughed half-heartedly at the memory.

“I’ve gone over all her notes and questions she had for Aunt Ammie. Grandma took this seriously. I wish I had.” “I’m guilty, too. I should’ve paid more attention. I thought it was another one of Grandma’s whims.” Tiffany took some of the papers from her mother and scanned the list of items. “Ammie’s not our real aunt, though, right?” “I’m not entirely sure. It was Mom who did all the work on that website.” Darlene’s face contorted as if the memory of the hours her mother spent researching was a bitter one. She tossed her glasses on the bed and stroked her face with her fingers before retrieving them again. “What was it called?” she said absently as she riffled through the sheets looking for the name. “DNA Strands, or something like that. Something science-y.” Tiffany nodded and eyed her mother as she pointed to a particular page. “Yeah, that’s it.” Tiffany plucked out the sheet. “She could be a distant cousin. Mom called her Aunt Ammie, and so will we when we get there. That’s what her granddaughter says everyone calls her.” “Just imagine turning a hundred and one,” Tiffany said. “I’ve never met a centenarian before. It will probably be a pretty tame party. Aunt Ammie, I like the sound of that, though. Amelia, right?” Darlene sat on the bed and tapped her finger on the notes. “How am I going to all of this?” She traced her finger down the page and stopped on an entry. “Yes, Amelia Nolan Power, born 1920.” “You don’t need to everything. Nobody expects that.” “I expect it.” Darlene laid the papers on the comforter and shoved her fingers through her shoulder-length dirty-blonde hair. “Everything is out of whack.” She grabbed the papers, set them on her lap with a thud, adjusted her glasses to hold them in place, and peered at the names again. Tiffany reached out but stopped short of touching her mother. She pulled away and hugged the pillow instead. “There are so many names. when Grandma got her DNA results and all those people first popped up in Canada?” she said gently.

Darlene straightened her back, pushed aside the papers, and laid her hands on her knees. She took a deep breath, then another, before offering Tiffany a flaccid smile. “Grandma said it was a miracle because so many showed up at once. She had me searching names for her online. Then she ordered DNA Strands DNA kits for the two of us, and that made her worse,” Tiffany teased. “Poor Grandma said she wanted to be sure that it wasn’t a mistake.” “Yes, when she set her mind to something, she followed it through,” Darlene said with another innocuous smile. She gazed at the ceiling and nodded slightly before resting her cheek in her palm. “ the time she took up quilting?” “Yeah, that’s why I don’t have a closet.” “I have two of them in here,” Darlene said as she patted the baggage. “That’s why the suitcase is so full. I thought it would be a nice gesture for Aunt Ammie’s birthday.” “That’s a good plan. Grandma would have wanted that.” Darlene pushed herself out to rest on the edge of the bed, then paused there before standing. “ the time she decided she was a senior and wanted to play bingo and bocce ball?” “Yep. I spent that summer on a lawn with her. Oh, and in a church hall. I was traumatized by the bingo hall. Who can forget the bingo hall? Not me!” Tiffany faked a shudder. Darlene laid her hand on the papers, pursed her lips, and slowly shook her head from side to side. “It’s a shame she never got to go. She’d have had such fun.” She wiped at another tear. Her voice softened. “I hope she knows I’m taking her. Even if it is a year later.” “She knows you. She knows you’d do what she couldn’t.” Tiffany reached out and squeezed her mother’s hand. “What about ‘Aunt Ammie’s’ family?” She airquoted the name for effect. “According to this Nikki lady, everything is arranged. We’ll be picked up in St. John’s in two days. We’ll arrive after midnight and stay at a hotel close to the

airport, where somebody will come for us the next morning.” “No car rental, I . We’ve talked about this a hundred times.” “It’s not a hundred, thank you very much.” Darlene looked at Tiffany beneath a hooded gaze as if to silence her, then continued. “I want to go over it again.” She paused, looked at the ceiling, and swallowed. “Nikki said a car will be available for us.” “But no car of our own. No way to escape, either.” Tiffany tipped her head sideways and gave her mother a wide-eyed look. That thought had crossed Darlene’s mind as well. “I know.” She gave Tiffany a pensive look and grimaced. “Come on, Mom. I was kidding. Same as last time you told me about it.” “She seems friendly enough from her emails,” Darlene said absently, while Tiffany rolled her eyes and cocked her head. “Let’s hope there’s no reason to escape.” Tiffany furrowed her brow. Her mouth became a taut line across her face as she gave her mother a pinched stare. “You really should try and enjoy this, you know. You’re off work. Grandma’s savings and insurance were meant for this. Try and make it a vacation. I can’t you ever having one.” “I had vacation. I just chose to spend it here with you and Grandma.” “That’s not the same. I really wish you’d, I don’t know, stop trying to be responsible for everything.” “I don’t do that.” “You’ve had this same conversation with Grandma about getting away by herself,” Tiffany went on. Then her tone softened. “You’re still a young woman. There’s a lot of room between now and—I hate to be morbid, but between now and death. That room is not meant for all work, or at the least no enjoyment. Maybe a quilting group like Grandma did, or do something social, something you could enjoy, and meet people.”

Darlene stared at her daughter. “I do more than work,” she said, her voice defensive, though she tried to make light of the remark. “Besides, we only have so much closet space for quilts.” “Tell me what you do.” Darlene tapped her bottom lip with her index finger. “I go to Ray’s for coffee,” she said. “Yes, conveniently just before the end of my shift. You don’t want me getting the bus home alone at night.” Tiffany paused. “Going for coffee can’t be the highlight of your life. I won’t be working at Ray’s forever.” She pushed off the bed and came around to hug her mother. “I’m not judging you. I’m concerned for you. Just like you were concerned about Grandma.” Stepping back, she added, “But please don’t go playing bingo. I’d draw the line there.” Darlene laughed and hugged Tiffany again. “Maybe that’s what we’ll do at Aunt Ammie’s party.” “We’ll have to leave, that’s all,” Tiffany said as she took an exaggerated turn and pressed her nose into the air. She looked over her shoulder at her mother, her brow wrinkled and tone grave. “I think I might even be serious about that.” “Ah, Tiff, what would I do without you?” “You’re not going to know until I finish college.” She pretended to punch her mother in the arm. “Got to put up with me for a few more years.” “I don’t want to think about that.” Darlene put her hands over her ears and sat on the bed. Moments later, she reached for her mother’s urn and rolled it between her palms. She slowly shook her head. “Time is really nothing. Mom couldn’t wait to see you go to college.” Tiffany squeezed her mother’s shoulder. Her face grew serious. “Mom, you’re not going to like what I’m going to say next, so I’m going to say it, then leave the room.” Darlene gazed up at her. Tiffany held her stare. “You are not the reason Grandma died. You are not responsible.”

Darlene’s bottom lip trembled, her lids drifted shut, and she let herself fall back onto the bed. The whisper of pants legs faded, and “I love you” was uttered before the door closed.

Darlene and Tiffany left Boston at 6:00 p.m., changed flights in Toronto, and boarded the three-hour flight to St. John’s. To calm her nervousness, Darlene took out the family tree printout her mother had prepared the year before. She had close to memorized it over the last week, but now confusion was setting in. “Grandma’s grandparents, that would make them your what?” “My great-great-grandparents,” Tiffany said quietly, startled from a doze by her mother’s voice. Tiffany’s heavy “not again” sigh had no effect on Darlene’s persistence. “So, according to Grandma’s research and the calculation from this DNA Strands place, one set of great-great-grandparents, Danol and Erith Cooper, indicates that Danol was born in New York but was a policeman in Boston, and Erith Lock had birth records tracing back to England. I’m not sure how or why they ended up in North Harbour, but anyway . . .” She trailed off. “The other grandparents . . . a Mary Rourke was born in John’s Pond and got married there in her late twenties to a Peter Nolan, also from John’s Pond.” She pulled the small printed map from underneath the papers and pointed to the red “X” marked on the island of Newfoundland. Tiffany nodded, and Darlene shuffled it to the bottom of the stack. “The Nolans were both doctors. Mary went to university in Boston. Aunt Ammie was born there, too.” “Okay,” Tiffany said as she stifled a yawn. “We’ll figure it out when we get there.” “Tiffany Emma Carter,” Darlene said. “Pay attention.” “I get it, lots of Boston connections. And whatever the relationship, I’ll call her Aunt Ammie without the air quotes.”

Seeing her mother’s serious face, Tiffany straightened herself in her seat. She rubbed her hands together in feigned excitement. “What else do we know about Aunt Ammie?” Tiffany stuffed her hands in her hoodie’s pocket and grinned as her fingers moved beneath the fabric. Darlene squeezed them through the polyester pouch and smiled. “Mary and Peter had five children—Edward, Peter, Catherine, David, and James. The junior Peter is Ammie’s father. Ammie’s father married Elizabeth Cooper, and they had seven children. Ammie is the eldest and is the only surviving sibling. Ammie married a Charles Power, and they had ten children. Her husband died when the children were small, so she raised them by herself. I don’t think they are all living. Nikki is the granddaughter of one of Aunt Ammie’s boys.” Darlene fidgeted in the seat as she ran her finger over the list on the paper. “Or maybe one of her girls. I can’t rightly .” “Does it matter? She’s a grandchild.” Tiffany reached over and stilled her mother’s hand. “Besides, what could be so interesting about any of them? I mean, beyond great-great-almost-a-hundred-and-one-year-old-aunt-slash-cousin interesting?” Darlene shook her head back and forth and laughed through clenched lips as she squeezed Tiffany’s arm. “I’m sure Aunt Ammie will lots of stories about them. Mary died sometime in the 1950s or ’60s. She was a doctor.” “Yeah, Grandma talked about that,” Tiffany said. “She also mentioned something about there being confusion whether she married a second Peter Nolan.” “That was one of Grandma’s questions.” Darlene pulled a sheet from the folder with renewed enthusiasm. “See, here it says Peter Nolan obituary and death notice. Two dates—1900 and 1958. She wanted to know which one was the right one, or if they were both correct. Though I don’t see how that could be possible.” “Grandma certainly had lots of questions,” Tiffany observed as she scanned the sheet, now resigned to engaging with her mother. “Grandma’s ‘evidence,’” Darlene said as she air-quoted. Her anxiety eased as they talked it through once more. She reached for Tiffany and gave her hand a

reassuring squeeze. At the bottom of the last sheet, Darlene tapped her fingernail over the capitalized word JOURNALS, which was followed by six exclamation points and a red circled “Mary and Peter.”

The loudspeaker crackled overhead, and the captain told them to prepare for landing. Darlene shuffled the papers into her mother’s portfolio, reached into her pocket, and clasped her mother’s urn. She tipped her head back to keep a tear from overflowing as she waited for the jolt when the wheels hit the runway. “You made it, Mom,” Darlene whispered, blinking the excess water away.

4

Nikki Wall met Tiffany and Darlene at the front desk at ten o’clock the next morning. “I have to warn you, it could get chaotic there. Family are arriving over the next few weeks, and we’re pretty loud. I’m not sure what you both are used to.” “Exciting,” Tiffany said. “How many are you expecting?” “There are about a hundred people coming from away, and the rest of us live near and far on the island. The hall holds three hundred, and we figure it will be full on the day of Nana’s birthday.” “How many are like us?” Darlene asked. “Like, from the US, or something else?” “Well, strangers. We haven’t met anyone.” “I believe you are the only two. I was sorry to hear about your mom, too, by the way. From the emails I received, I believe she would have enjoyed this.” “Thank you,” Darlene said. “I’m sure she would have. So, it’s only us here for the first time?” Nikki nodded several times as if she were counting down a list. “Yes, some haven’t been home in a few years. Well, last year doesn’t count. But for the most part, they are all family we know. Usually, every five years, everyone makes an extra special effort. We call them ‘Come Home Years.’ It’s a thing here in Newfoundland. Usually for a community, but we do it for family,” Nikki said, making a swipe at the air with her hand. “We were heartbroken when her hundredth was cancelled due to COVID lockdowns. Nana said she was born in a pandemic and she wasn’t going to die in one. Now with Nana turning a hundred and one, as many as possible are coming.

We’re all just happy she made it. We miss parties and get-togethers, too, and we’re glad we didn’t have to cancel this one.” “Do you think it might be best if we stayed in the city or a hotel in the area until the party? We might be tresing on your reunion.” “Are you kidding?” Nikki said as she gazed back at Darlene and then glanced at the back seat. “Nana would kill me if I let you do that. Besides, there’s nothing close, and she has rooms ready for you both at her house.” “Really?” Tiffany asked, her voice high-pitched. “Yes, of course. Nana said that you might not feel involved or welcomed if we put you in one of the trailers. She wanted you front and centre. She’s so glad that family from away has found her.” “From away?” Tiffany and Darlene asked in unison. “Oh,” Nikki laughed. “Yes, if you are not from here, you’re from away. Nana said that’s the best part of her birthday.” Darlene and Tiffany glanced at one another. “Okay,” Tiffany said. “So, we’re from away?” “Yes. Did you hear tell of Come From Away, the Broadway musical?” Tiffany’s look of surprise made Nikki laugh. “Seriously,” she said as she bobbed her head. “Anyway, you don’t know Nana, but what she wants, she gets. So, no sense trying to change her mind. You’re in the house, and that’s that.” Nikki gave them a pointed tour on the one-hour drive and promised she’d be available to bring them to any places of interest they wanted to see the week after next. “I’m also doing a big heritage project with the school kids next year, so I’m going to be a parasite.” “Parasite?” Darlene asked.

“Yep. I know your mother was looking for family history, and I’m going to use that next year for the project. If you don’t mind, of course. I’ll work with you both and take notes from Nana’s memory and read the journals she has in the trunk. I have an appointment for us at The Rooms in two weeks. If you want to go.” “The Rooms?” “Our archives in St. John’s.” “Oh,” Tiffany said. “Yes, I’d love to go. I’m sure Mom would, too.” “Yes,” Darlene said. “I’m in. We’ll follow your lead. Journals?” “Yes, you can go through them this week when nobody is around, if you want. They are from the 1900s, mostly. After the war, Mary and Peter stopped writing them, as far as we can tell. I had the war ones for a school project last year, but I haven’t read the rest. So, this summer, that’s what I’ll be doing.” “Are you sure we can’t stay at a hotel in the community?” Nikki laughed. “You will understand when we get there. And we’re here. This is North Harbour,” she said as the trees opened out onto the ocean. “Both sides are considered North Harbour, but the other side is a dirt road and mostly cabins now. I don’t know if you can make out the path over the hill across there, but that’s the road to John’s Pond. We’ll take Nana over there before her birthday. We’ll have a boil-up . . .” Nikki noticed the blank look on Darlene’s face. “I guess you would call it a family picnic.” “That sounds like fun. We’d love that. It will remind me of Grandma and bocce ball,” Tiffany said. Darlene nodded, and they both shared a nervous grin. The road edged the harbour, and with the tide high, it was like they were travelling by boat. “Pretty neat, hey?” Darlene and Tiffany nodded as they went over a small rise and Nikki slowed. A large two-storeyed house with a gabled roof was a bright fresh white against the green mosaic of the surrounding grass and trees. Double bay windows from ground to roof on both sides of the house gave it a bold character. In the meadow, there were eight mobile trailers in a line, huddled side by side near the

driveway. Cars and trucks were spread out across the meadow. “Looks like a full house,” Nikki said. “Family are staying in the trailers when they arrive. Some have cabins on the south side or actually live here in the harbour. Like I said, we are a loud bunch and can be overwhelming, especially now that we’re finally allowed to gather together.” She laughed. “Don’t let anyone scare you off. After the initial greetings, everyone will go on about their business. There’ll be lots of meals, food and people coming and going, but that’s what Nana wants.” Darlene looked at Tiffany, her raised brows and wide eyes behind her glasses seeking reassurance from her daughter. However, Tiffany, with her forehead on the glass, was busy surveying the area. Darlene settled in her seat and waited for Nikki to park the car. They were swarmed by kids, from toddlers to teens, and two men came to take their bags. Nikki introduced them, but the names were forgotten soon after they were spoken. The gravel beneath their feet skittered away as they trod to the rear of the house, a trail of chattering children skipping all around them. “We’re intruding,” Darlene said, her stomach knotted and clenched. She reached for Tiffany’s hand. “No, you’re not. Honestly,” Nikki reassured her. As they rounded the house, Darlene caught sight of several men in the distance playing horseshoes near the barn. The few who were facing them waved, and the ones who had their backs to them turned and shouted greetings. Darlene gestured hesitantly and awkwardly as she followed Nikki across the threshold and in through the porch. She heard voices but saw only black and blurred images after going from brilliant sunshine into the darker interior on the way the kitchen. Somebody told the children to go outside for a bit. Darlene sidled toward the wall while arms and shoulders skipped and rushed past her in the porch as the kids exited. She kept following Nikki until her blackened silhouette stopped. Darlene’s eyes gradually regained sight in a brightly lit kitchen. An old-fashioned stove was the centrepiece. Kettles atop it were steaming and spitting. Pots of food lay covered on the oven door and on the warmer. Smells of meat and vegetables hung in the air, and her stomach, to her chagrin, growled in appreciation.

A larger woman, strikingly an older version of Nikki, cracked eggs into a frying pan on the polished iron stove. Darlene’s mouth opened in a silent gasp. She put her fingertips to her lips to cover her astonishment. In that moment, she believed she’d stepped back in time. Nikki kissed the woman’s cheek. “Auntie Rose, I didn’t realize you’d be here.” “Somebody has to cook for this bunch,” the woman said with a smile. She looked toward Darlene and Tiffany. “Welcome to you. I’m sure you’ll be hungry. Ham and eggs are the order of the day.” “Thank you,” Darlene stammered. “I hope you don’t mind the noise,” Rose said. “We got a fair share of it here today.” Darlene’s pasted smile didn’t leave her lips as she gazed around the room. A tall man was helping an old lady from the rocking chair in the corner. Once she straightened, he let her go, and she scuffed across the kitchen toward them. Every eye in the room—and there were many—was fixed on them. “I’m Ammie,” she said as she held out her hand. “Most folks call me Aunt Ammie or Nana.” Darlene and Tiffany moved forward to meet her. She didn’t immediately take their hands but moved her fingers instead along Tiffany’s red hair as her eyes brimmed with tears. In the coveted silence, Ammie lived out some long-ago memory. Her eyes changed with the waning intensity of the recollection, and she returned to the present. “You’re the spit of my grandmother, Mary,” she said breathlessly. “From my earliest memories, her hair was the colour of yours.” Tiffany blushed. “There’s no mistaking, you’re our family,” Ammie said with resolution as she held their hands. Darlene was surprised by the strength of her grip. She pulled each of them to her and hugged them. “Aunt Ammie,” Darlene said slowly and waited for the barely perceptible nod of acceptance from the woman.

“I’m truly sorry to hear about your mom,” Ammie said, her piercing eyes taking in the two women. She patted Darlene on the back and gave her another hug. “We were saddened to hear about her.” “I appreciate that,” Darlene stammered as a sudden and jarring grief punctured her equilibrium. Tears threatened to spill over and drench her, but in an attempt to quell the emotions, her inner voice warned of first impressions and embarrassment among strangers. Being unable to reign in a sadness that she thought she’d been able to internalize scared her. “We miss her every day.” She tensed to dam off the flooding sentiment that was threatening. “She was looking forward to meeting all of you,” she managed as she dropped her right hand and drummed her fingers along the cotton of her slacks. Her lips clamped tight against the quiver of emotion, and she focused on the empty space between Ammie’s shoulder and the wall. Darlene dug her nails into the heel of her hands to realign herself. With intent, she failed to mention her mother was here with them, in an urn in her loose-fitting pocket. That fact would remain private for her and Tiffany. If spoken aloud, it would make it real, a little voice niggled. Ammie nodded and gazed at Darlene, taking in the struggle in her eyes. “We were luckier than most in that regard. Awful thing, that COVID. I was never in a hurry for the future until last year.” She squeezed Darlene’s arm and searched her face once more. Ammie paused, and her eyes took on a comionate glow. “That’s enough about that now. We all know what it was,” she chided herself. “We’re glad to get back to this . . . noise,” Rose said as she prepared plates. Ammie gestured around the room. “This is my house, and you’re welcome here any time. We are all so glad you came.” Affirmations rose like a hummed chorus from around the room. “It’s not every day that a girl turns a hundred and one.” She smiled. “We are honoured,” Tiffany said, expressing each word with an air of importance. “I’m happy that I remind you of your grandmother.” “It’s quite remarkable, actually. Grandma Mary on the sod,” Ammie said as she reached out and stroked Tiffany’s hair once more. “Come. Sit at the table. Have a mug-up for yourselves. I’ll you.”

Sensing their confusion, Nikki motioned for them to follow Ammie as she took the plates from Rose and deposited them on the table. “You have so many people here. I’m sure you could use the room for somebody else,” Darlene said, her composure holding fast. “Nonsense. I won’t hear tell of it,” Ammie said. “You don’t know anyone around here. What better way to get to know them than being plunked down in the middle of them?” She grinned, and several people chuckled. Darlene glanced around to get a bearing on the place. The walls were lined with men and women, some seated, some standing, but all looking on. She nodded without meeting anyone’s eyes and then focused on the table. Ammie shuffled along. Tiffany helped with her chair, and they sat on either side of her. Six others were already seated and eating. They were introduced, and Darlene apologized for being sure she wouldn’t any names. They laughed, and Darlene dug into the ham and eggs to hide her unsettledness as much as to assuage her hunger pangs. Ammie pointed toward the loaf of bread. Tiffany, who seemed right at home and not at all out of place, reached for a slice without hesitation. “It’s still warm, Mom.” “Not long out of the oven,” Rose called from the stove. “Nice and fresh for you.” Tiffany took a bite and smiled. “Oh my, I’ve died and gone to heaven. Mom, you have to try it.” Darlene reached for a slice after Ammie smiled and gave her a raised eyebrow and sidelong glance toward the bread. After the first bite, she had to agree with Tiffany. She smiled as she chewed and savoured the warm delicacy. “There’s lots of local jams in the cupboard for you to try during the week, too,” Rose said. Ammie asked about their flight. They made small talk. There was laughter and joviality around the table and in the room. Some things were said so quickly, Darlene couldn’t understand them. People got up, others sat down, introductions

were made once again. “This place is more efficient than any restaurant I’ve been in,” Darlene blurted out in wonderment as they greeted the new additions to the table. Somewhere between the first bite of bread and the last forkful of eggs, the tension that had woven her tight for days dissipated. She didn’t have time to examine when or how it happened. “Rose has this shift. Tess takes the next one at suppertime,” Ammie said. “We did this when I was ninety and ninety-five.” “We’ve been doing this since you were eighty,” Rose said as she laid a plate in front of one of the newcomers. She leaned in over Ammie and kissed the top of her head on her way to the stove. “Every five years it’s a bigger affair,” she said. “And we love it because it brings us all together. We need it. Last year was another story, and we all choose to forget it.” Rose brought the teapot over, then the coffee pot. Darlene and Tiffany had the latter. A young man in his late teens came in looking for one of the boys. “Hello, Aunt Ammie,” he said as he pecked her on the cheek. It was so natural the way he held her hand while he spoke to the others. When he learned the boys were in one of the trailers, he bent and hugged her. “I’ll be back later.” He patted her hand. “I’m Stephen, by the way,” he said to Tiffany and Darlene. “I live at the other end of the harbour.” He shook their hands and turned to leave. “Want something to eat?” Rose called after him. “I’ll come back,” he shouted from somewhere in the yard. “Nice boy, that fellow,” Ammie said. “His mother comes here twice a day in normal times, even last year in lockdown and bubble times.” Rose saw the confusion on Darlene’s face. “His mom, Karen, is Nana’s care worker. She comes and helps Nana with lunch and supper. She was here last year when we couldn’t be.” “Nice woman, that one,” Ammie said. “She’s been bringing young Stephen here for almost twenty years. He’s one of our own.” “He’s a relative?” Tiffany asked.

“No, not related that we know. But he’s been coming here so often, he’s like one of mine,” Ammie said with a smile. “Now I think I’ll get in the rocker.” Rose came to assist her, and Darlene stood and moved Ammie’s chair out. “Thank you, dear,” Ammie said as she smiled at Darlene. The warmth of Ammie’s hand on hers on the back of the chair was settling as the tension threatened to take hold of Darlene once again. Ammie had a charm about her that was infectious. Darlene resisted the urge to hug her, which had sprung from some unfamiliar quarter of her being. Nikki said, “I’ll show you upstairs. Bathroom, stuff like that.” Darlene nodded, grateful for not making an awkward scene standing by Ammie’s rocker. Stephen and two boys came in and sat down. Tiffany was pushing away from the table when Stephen asked her a question. She smiled at her mother and remained with the younger gathering. “Don’t mind the busyness around here today,” said Nikki. “Tonight, most of the crowd will go home to St. John’s and return next weekend. Me included. I work next week at the school finishing up for the summer. But then I’m off, so I’ll be back. Stephen has offered to chauffeur you this week. And the car is there for you to use whenever you want.” “This is too much,” Darlene said as she followed Nikki up the stairs. They ed a wooden rail, where Nikki showed her the room. Striped wallpaper of burgundies and roses complemented the deep maroon hardwood floor. A queen bed with a soft pink covering was layered in pillows. An ancient brown trunk at the foot was covered by a lace doily. As she moved farther into the room, she noticed the window seat in the alcove overlooking the harbour. White sheers were pinned by tasselled, crocheted ties. She gasped. “I’m sure some of the family should be here.” “Nonsense. You’re family. Don’t give it another thought. Nana is across the landing. She likes to see the sun rise on the harbour in the mornings, too. It can be quite spectacular.” Nikki smiled. “Oh, and we ed the bathroom at the top of the stairs. Tiffany is in the room on this side of the hall, and the other one is free for the moment. I think that will change next week, though. It depends on whether Uncle Ronnie brings his trailer. We’ll see.” “So, Aunt Ammie lives here by herself?” Darlene’s eyes widened at the thought.

“Yes, that’s right. Karen comes twice a day, and some of us take turns staying here on weekends. The trailers will be empty, at least this week. I’ll be here for the rest of your stay starting next Friday. Our trailer is the closest to the house. Brian didn’t come in this weekend but will be here for the party. Oh, Brian’s my husband.” Nikki laughed. “I forget you haven’t been here before. Please ask all the questions you want. If you’re up for a walk, Stephen will bring you to John’s Pond on Tuesday. The road’s a little rough, so we generally walk or bike the five kilometres. We’ll bring Nana and the supplies over on bikes when we have the —” She paused as if searching for a word. “The picnic.” “Aunt Ammie rides a bike?” Darlene asked, her voice raised at the notion. “Yes,” Nikki said. “Oh, not the kind of bike you’re thinking of. It’s an all-terrain. A side by side, something like a truck with big wheels.” She laughed. “I forget you’re not acquainted with things around here. Anyway, Stephen wants to take you. By how quick he came back into the house, I think he’s taken a shine to your daughter.” “Oh,” Darlene said. “I didn’t notice.” “Any other time, they wouldn’t come in at all.” Nikki laughed. “We’re not putting him out this week?” “Stop worrying. You’re guests and family. But if you come back next year, you’re on your own.” She laughed again and squeezed Darlene’s arm. “Seriously, you’ve found us now, and it might be hard to get rid of us.” Darlene smiled. She brushed her hand over a knitted afghan at the foot of the bed and looked at the shades of black and white pictures on the far wall. “I’ll leave you to it,” Nikki said. “We’ll see you downstairs when you’re ready.” “Family,” Darlene whispered to the walls as she scowled and shook her head. How easily they seemed to have claimed her and Tiffany without knowing anything about them. “Why did you have to start this, Mom?” she mouthed to the ceiling. An irrational thought swept through her mind to take her daughter and run. She squeezed her lids shut to dispel the urge. She couldn’t, of course, she reasoned—

she didn’t have a vehicle. Darlene closed the door, sat on the bed, and let her emotions loose.

5

The next morning, Darlene peeked in at Tiffany. She was fast asleep. The steady rise and fall of the patchwork quilt was a comfort to Darlene. Her mind flashed to Tiffany’s youth, when Darlene would come home from work and watch Tiffany through the crack in the door. Her mother would be asleep on the couch, and Darlene would cover her before going off to bed. She shook her head to disperse the herd of pensive thoughts. She’d slept surprisingly well. The silence here was so different. Silence in Boston was beset with honking horns, sirens, and an underpinning drone of the city—all turned into a false-silence reality. Yesterday, the first families said their goodbyes around 2:00 p.m., with the last having left after supper, all returning to work or the final week of school in St. John’s or other places. Ammie was in bed by 8:30 p.m., and Darlene and Tiffany were alone in the kitchen preparing to follow. Tiffany had a wondrous smile on her face when she looked at her mother and said, “I can’t believe we’re here. What a day. This is our family.” “Yesterday was a whirlwind. It is hard to believe.” “Mom,” Tiffany said, “please promise me you’ll give this a chance.” “I’m here. Of course I will.” “No, Mom. I mean really give it a chance.” Tiffany eyed her mother. “I know you, . Promise me. Say it out loud.” “Tiffany,” Darlene scolded. “Say it. Please,” Tiffany added softly.

They stared at each other before Darlene said, “Promise.” Her lips spoke what her heart didn’t believe. “I’m going to hold you to it.” “I promise, Tiff. Honestly.” “The promise is not for me,” Tiffany said as she put her hand on her mother’s shoulder. “It’s for you. I already believe. Night.” She bounded up the stairs before Darlene could answer. A little later, lying in bed, Darlene thought of Tiffany. She saw a younger version of herself worrying about her own mother a year or more after Tiffany was born. The worry didn’t stop. Then her mother’s smile the last morning she’d left for work entered her thoughts. Mom had embraced this notion of finding family. Darlene had been wary of it, didn’t understand it, and hadn’t tried nor helped. But her mother had done it like she had done so many other things. Fearlessly. Now with her mother gone, she was propelled into an uncomfortable state that not only did she not understand, but maybe she didn’t want to understand. Tiffany sensed this. Darlene could either stay here and bide her time until they returned home or be like her mother and launch herself into the experience. She reached for the urn on the nightstand and sighed. For Tiffany’s sake, she would do the latter. Maybe even for my own. Darlene fell fast asleep and woke with the determination that this would be an experience Tiffany wouldn’t forget. She took another peek at Tiffany, who was still sound asleep. Ammie whispered her name from across the hall, and Darlene nearly jumped out of her skin. Then she grinned at Ammie’s smile. “Sorry,” Ammie whispered. “I got a fright when I saw you, too. I forgot you were here.” She made her way over the hall and linked her arm into Darlene’s. “It’s good to see you. Good morning.” “Good morning,” Darlene whispered. “It’s so quiet and peaceful here.” She pulled Tiffany’s door shut and guided Ammie to the stairs, going down ahead of

her. “Have you ever made a fire before?” Ammie asked. “I don’t believe I have. I’ve never been camping or anything. Mom wasn’t the outdoor type until she was in her sixties.” “Well, there’s always something to be learned in a day,” Ammie teased. “The splits and shavings are made. We only have to set the match.” “I believe I can do that,” Darlene said with an exaggerated wink. “You just need to explain what’s a split and what’s a shaving.” Ammie laughed. “I think we’re going to get along just fine.” Darlene, under Ammie’s guidance, placed the shavings in the firebox and lit the match. When the third one blew out in the draft, she handed the box to Ammie. Darlene blushed, and Ammie smiled. “Cup your hand around it like this,” she said as she struck the match and sheltered it in her palm. She blew it out and handed the box to Darlene once again. Darlene smiled widely at Ammie when she successfully lit the spalls, and once the flames were going, she laid in the splits. Ammie pointed out a pair of white cotton gloves and told Darlene to put them on. Darlene fetched small junks from the woodbox and crossed them over the splits so as not to put out the flame. She closed the stove door, pulled off the gloves, and brushed her hands together. “My first fire,” she said with a grin that put an odd feeling in her belly and made her cheeks twitch. “What’s next?” “The kettles could use fresh water. Wait. Today is Monday. One kettle will do with enough water for the three of us. We can fill it after we have our tea.” Darlene poured the water from the kettles and refilled one and half-filled the other. Ammie added more wood and left one damper open over the flame for the lighter kettle. The other one, shining silver but for the blackened bottom, she directed Darlene to place on the back of the stove. It would simmer there and be hot for lunch.

“Poke around and figure out what you want for breakfast. There’s ham left over from yesterday. Bread’s in the cupboard, eggs in the fridge. Please yourself.” “What would you like?” “I’ll have whatever you’re having. Unless it’s fancy stuff that I can’t pronounce or never heard of,” Aunt Ammie qualified. “I draw the line there.” “How about boiled eggs and toast?” “That would be right nice,” Ammie said. “Now, listen here. I don’t expect you to come here to tend on me. I’ll allow it for this morning, though.” Her last sentence was uttered while peering at Darlene under hooded brows. She pursed her lips to smother a grin. Darlene chuckled. “We have to do something to earn our keep. You can take advantage of that.” She asked where to find the dishes and food, and Ammie directed her from her seat in the rocking chair. “We could be a symphony,” Darlene said. “You point, and I’ll go.” When the place was set and they were both seated, Ammie laid her hand on Darlene’s. “I was truly saddened to hear about your mother, Emma. I know how difficult it can be.” “Thanks, Aunt Ammie. I know it’s been more than a year, but it seems like yesterday.” “It helps to talk about her. Tell me about your mother and why she was looking for us.” “Mom was raised in a series of foster homes in Boston. She always said she wasn’t connected to anything until I was born. We didn’t have it easy with her a single mom, but she always made me feel special and loved.” Darlene stared at Ammie as she spoke. “She worked two and three jobs to keep us off the streets. It was harder when I was small, but when I got old enough, she’d work somewhere I could go with her, like a café or a library. I started helping out when I was twelve or so. It wasn’t as hard then. We both went to work at Ray’s

Diner when I was fourteen, saved, and with the help of scholarships, I went to university and got a degree.” “That’s wonderful. You must have made her so proud.” “Well, when I was in school, I had Tiffany. The guy wasn’t interested in ‘playing house,’ as he put it, so at twenty-one I had become like my mother, a single parent. The only difference was I had her. She wouldn’t hear of anything other than my finishing what I started and her staying home with Tiffany until she was old enough for school. I worked and went to school part-time up to when Tiffany was six. We lived together until last year, when COVID-19 hit. Mom got sick at the diner, and within two days, she was in hospital.” Darlene stopped before saying the rest. To say it aloud seemed like it would make it truer than the reality they were living. Ammie took both Darlene’s hands in hers and squeezed them. Darlene held the anguish behind clenched lips, and only one treasonous tear released. “I still can’t believe it. After a year, you think I would.” “That’s not how things work. Look at the year we all had. It’s not a race. You’ll have fond memories in time.” They heard Tiffany on the stairs. Darlene wiped at her eyes and reached for her coffee, glad to finish the conversation. “That was a great sleep,” Tiffany said as she twisted and stretched her back and arms. “I hope you slept well.” She came around the table and kissed the top of her mother’s head and then did the same with Ammie. Ammie patted the table on the other side of her. Tiffany made a cup of coffee, grabbed a plate from the cupboard, and sat down. “It feels like home, just in a different place. The sentiment is here,” Tiffany said as she bit into a slab of bread. “Try the partridgeberry jam.” Ammie’s bony finger pointed to a cupboard behind Tiffany. Tiffany fetched the small jar and opened it. She wrinkled her nose at the tart aroma but spread it on the bread just the same. “I think it will grow on me.” She

offered some to her mother and Ammie. “What are your plans for the day?” Darlene asked. “Stephen is coming over to help us piece together who we are,” Tiffany said absently as she chewed the last bite of her bread. “The graveyard is over the next rise. Stephen can show you where many of your kin are buried. I have journals in the trunk in your room I want you to read.” “The trunk in the room I’m in?” Darlene asked. “Yes. It was my grandmother Mary Nolan’s trunk. She brought that from Boston before I was born. She gave it to me when I got married.” “Oh, wow,” Tiffany said. “I want to see that, Mom.” “There’s journals from Mary’s life in John’s Pond, and Peter’s life. They stopped writing, as far as I can tell, after the First World War. That’s after they came back from . . .” Ammie stopped. “I’ll wait a few days before I say anything. It’s better if you read first. This will be a quiet week, so it’s a good time to get at that.”

Stephen helped them retrieve journals from the trunk. There were various colours and sizes of hard-bound books displayed on the table. Different sizes and thicknesses were marked by year. “I want to read Mary’s, since Aunt Ammie says I look like her,” Tiffany said. “I’ll help you take notes if you want,” Stephen said. “This is like the greatest hunt ever. Like solving a real-life mystery.” His enthusiasm was genuine. Tiffany smiled at him. Darlene made a mental note that perhaps Nikki was more perceptive than she thought. “Fine, I’ll take Peter’s.” They separated the books in piles by years and agreed to start with the oldest first. Tiffany and Stephen stayed in the house and later laid a quilt out on the grass near the old barn.

Darlene grabbed a cup of coffee and brought her first journal to the front veranda. She laid the cup on a little table and a cushion on the wooden chair. Ammie grinned at her through the window. “Are you sure you don’t mind being in there by yourself? I can come back in.” “I’m all right where I am, and so are you,” Ammie said through the glass. Darlene settled herself into a comfortable position and picked up the journal. “Now, Peter Nolan, what’s to discover about you?” A warm breeze ruffled her hair as she lifted the cover.

6

Spring 1895

Dr. Peter Nolan moved about the ward at the General Hospital in St. John’s. He smiled and conversed with patients as he checked them over, gave them updates, or discharged them. This routine helped him keep his focus and settled his thoughts of self-imposed wrongdoings that haunted an idle mind. It wasn’t that he was amassing good deeds to outweigh the transgressions, or that he thought forgiveness would be easier if his actions were counted. Forgiveness started with himself, and he was the only one keeping score. He often wondered how much was enough to lance the hurt he’d inflicted with choices he’d made. But he knew the answer and had to live with it. There was no way to tally “enough,” and that was the part that needed a busy routine, that needed settling. He’d been a ship’s surgeon until eight years ago, when he moved to St. John’s and married Martha Walker. She was an English girl who had fallen in love with his brother Ed. When Ed died tragically, Martha learned she was pregnant. With no home and no future, he couldn’t have his only living relative destitute in a foreign land, so Peter did the only thing he could—he married her. Now his wife was gone almost a year, and he had a fine stepson named Eddy. Though he hadn’t entered into any physical relationship with Martha, he missed her company, especially when she was having good days. Caring for Eddy hadn’t brought her back from her grief, and Peter believed she’d died from a broken heart. Eddy’s live-in nanny, Mrs. Mallard, had been a godsend. Herself a widow, she was happy to find employment in his household. She had saved them all in many ways. Eddy had a normal childhood, Martha had help on days she couldn’t get out of bed, and Peter had peace of mind knowing they were all well cared for. Mrs. Mallard continued to stay with them and had no plans to leave. For that, more than ever, he was grateful.

Then there was Mary Rourke—the woman who haunted his dreams, who occupied many of his waking hours, especially now that Martha was gone. Out of respect for his wife, he would wait a year before pursuing any other relationship. The only one he wanted was Mary. Peter wouldn’t soon forget her face the day he told her he would marry Martha. He couldn’t tell her he was stuck in duty. He’d had every intention to marry her, have a big family and a loving home. He had made something of himself, but the only thing missing was Mary. “Get out of here, Peter. I never want to see you again,” had been uttered from her lips. He’d wanted to reach for her, tell her everything, but he couldn’t. It wasn’t fair to her nor to Martha. So, he’d remained silent. Martha hadn’t been a burden. It wasn’t right for him to think that. He’d missed his chance at being happy because of the duty he’d carried for family. It was his choice, not Martha’s circumstance. He was to blame. Now, Peter couldn’t help but think that he could finally have what he’d wanted those many years before. However, Mary was probably married. She probably didn’t want to see him. She probably still hated him. None of these things could give blame to her. There were so many unknowns that he wasn’t sure if he could live with a new rejection for the rest of his life. But there was a lot of “rest of” left in his life. How could he bear to be alone with the love he still carried for Mary Rourke, known locally as Mary Ro, without knowing if it could be returned or not? How many distractions could he find to keep himself from going insane if her answer was no? His dilemma was fresh and tresing on his strive for resolve, especially since Martha would be gone a year on March 1. His ever-present realization that devotion to patients could only provide so much distraction kept him offbalance. “Dr. Nolan, when you’re ready, a word, please,” said Dr. Abraham Hart, the senior physician at the General Hospital. Peter finished up with the parents of the young boy who’d suffered a broken leg and met Dr. Hart in the corridor. “Peter, there’s an ongoing tragedy unfolding in Trinity Bay. A doctor has been

requested to the SS Ingraham. I want you to go. You have the most experience of the lot here for injuries at sea.” Dr. Hart knew that Peter had started out as a surgeon’s assistant on the SS Frisia, part of the Hamburg-American Line, and later was promoted to ship’s surgeon before he returned home and ed the General Hospital. “How much time do I have?” “Precious little.” “I’ll go now.” “Peter, Loretta’s people are from out there. Do what you can.” “Of course.” Peter had met Loretta Hart on several occasions when there were societal functions that required the doctors and their wives to be present. She was a bit odd and pretty much remained at her husband’s side, not mixing with the other wives. Peter, thinking she was quite shy, always made an effort to speak to her despite the initial clumsiness of conversation. He was able to build a relationship with her that stripped the awkwardness that others found off-putting, and he became comfortable in the Harts’ company after that. Dr. Hart had confided in him that the couple had had four babies after their first daughter, Geraldine, was born. However, the rest had died as infants. Loretta hadn’t been the same since then, according to her husband. Peter introduced her to Martha. They developed a friendship, but after Martha died, Peter didn’t see much of Loretta. Peter went by the house and explained the situation to Mrs. Mallard. She’d become accustomed to his goings and comings. He packed a few items to keep him warm and dry, including extra wool socks. He took his medical bag, said goodbye to Eddy, and headed for the ship in the harbour. Before long, they were steaming out through the Narrows, heading for Trinity Bay.

7

Wind whipped snowy ghosts over their heads and out across the ice. Peter couldn’t be certain if it was an omen of things to come. Behind the haunting trail, a squall uprooted the ocean and drenched them in frozen spatters that clung to them like webs and layered on everything else it touched. Three men struggled at the wheel to keep the Ingraham from hitting the white field side-on and upsetting her. “Just a little more, lads!” the captain yelled. “Easy, now. Easy.” He nodded at Peter. “It’s a foolhardy thing you’re attempting.” “Not for the people who need help.” “I fear the only one who’ll need help is you.” Peter contemplated the sentiment, which, if he were truthful with himself, mirrored his own thoughts. He smacked his heavy mittens off his thigh as if the sting could banish the lingering doubt. “I’ll write a note relieving you of responsibility for my actions,” he said. The captain had been trying to dissuade him from what he believed was certain death. “To be clear, I’m going, with or without your . I’d like it to be with it.” “I need all the men I have to fight this storm if we have any hope of getting back to port.” “I understand. I wouldn’t ask anyone to risk his life.” The captain shouted orders at the men. He turned to one of them. “Anything on the wire?” With the shake of Riley’s head, it was sealed. “Perhaps they’re all home safe,” the captain suggested. “I’m no fool, and neither are you.” Peter’s challenging glare caused the captain

to study him once more. “You know different. We would have heard.” The captain nodded, then gazed at the icy boards beneath their feet. “Over a hundred men out in this, unprepared. I allow you’ll be going to bury the lot of them. That’s if you make it, yourself.” “I hope otherwise for the men. But if it comes to that, so be it.” Peter cast a glance over the harsh, white landscape. “If I can save even one, it will be worth it. I spent a year farther north than this. I’ll be all right.” The crew had tried for hours to penetrate the wall of ice at the mouth of the bay. A pan stretched from north of Bonavista to Baccalieu Island in the south. After many attempts to forge a path, and with worry of damage to the hull, the captain declared it was too thick to break through. The captain wired St. John’s requesting the larger Labrador be deployed. That meant a day or more delay—with no guarantee the Labrador would get through, either. The sudden and bitterly cold northeasterly wind continued to blow the ice on the land for the second day. Hundreds of men were out in small skiffs and dories, and many were still uned for. Peter knew his medical skills would be needed. He couldn’t turn away from that duty. With great care, the ship sidled toward the ice, and the crew lowered a small, flat-bottomed boat. The captain gave Peter several flares. “Good luck, son. May the Lord have mercy on you and guide you safely ashore.” The ship creaked and groaned, battling the harsh elements, as the men turned her toward St. John’s. Peter watched her stern for a few moments as she disappeared into a stormy whiteness, as if a painter had swirled the brush and erased the ship, leaving a colourless canvas. Peter got his bearings from the com and set out. He pulled the boat across the ragged ice island, stopping often so as not to raise a sweat. The wind whipped at his back as he trudged for three miles to the open water of Trinity Bay. In the waning light of the day, he turned the punt onto its side in the shelter of a six-foot ice stack that was several yards from the edge. The sea was calm