Torts And Damages Midterm Reviewer 5j64n

This document was ed by and they confirmed that they have the permission to share it. If you are author or own the copyright of this book, please report to us by using this report form. Report 3i3n4

Overview 26281t

& View Torts And Damages Midterm Reviewer as PDF for free.

More details 6y5l6z

- Words: 13,669

- Pages: 42

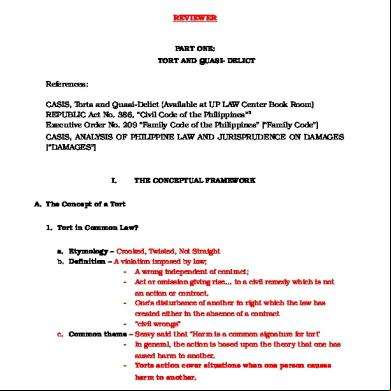

TORTS AND DAMAGES REVIEWER

PART ONE: TORT AND QUASI- DELICT

References: CASIS, Torts and Quasi-Delict (Available at UP LAW Center Book Room) REPUBLIC Act No. 386, “Civil Code of the Philippines”2 Executive Order No. 209 “Family Code of the Philippines” [“Family Code”] CASIS, ANALYSIS OF PHILIPPINE LAW AND JURISPRUDENCE ON DAMAGES [“DAMAGES”]

I.

THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

A. The Concept of a Tort 1. Tort in Common Law? a. Etymology – Crooked, Twisted, Not Straight b. Definition – A violation imposed by law; - A wrong independent of contract; - Act or omission giving rise… to a civil remedy which is not -

an action or contract. One’s disturbance of another in right which the law has

created either in the absence of a contract - “civil wrongs” c. Common theme – Seavy said that “Harm is a common signature for tort’ - In general, the action is based upon the theory that one has -

aused harm to another. Torts action cover situations when one person causes harm to another.

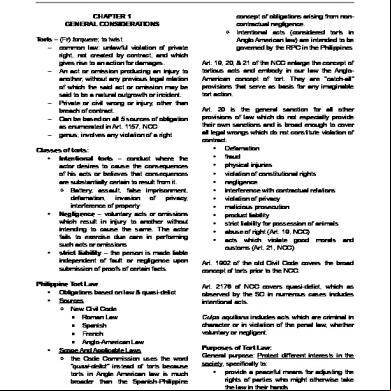

2. “Tort” under Philippine law

a. Existence of “Philippine Tort Law” i. Intent of the Framers – was to reject the term “tort’ in favor of the term “quasi-delict”. - It was agreed to use if the term “quasi-delict and rejected the term tort” because the former best describe the civil action for damages envisioned under the proposed code. The latter was rejected because the common law concept overed far -

more that what the Commission envisioned. The original plan was to exclude intentional and malicious acts from the coverage of the concept because these are to be governed by the Revised Penal Code.

ii. Civil Code Test Article 1902 Old Civil Coder (cf Article 2176 Civil Code) “Any Person who by an act of omission causes damage to another by his fault or negligence shall be liable for the damage so done.” Art. 1902 of the old Civil code – the exact definition/description of a tort. Article 2176- “Whoever by act or omission causes damage to another, there being fault or negligence, is obliged to pay for the damage done. Such fault or negligence, if there is no pre-existing contractual relation between the parties, is called a quasi-delict and is governed by the provision of this chapter.” -

Even if the tort was rejected in favor of the term quasi-delict it did not completely reject the concept of tort as evidenced by the civil code.

b. Scope of Philippine Tort Law

-Although the tort is never used in the civil code, “tort” as a concept is reflected in a number of civil code provisions… Thus, the exact boundaries of Philippine Tort Law are unclear. - Antonio Carpio accepts that tort and quasi-delict are two distinct concepts coming from two different legal traditions, he considers quasi-delicts as forming one area of Philippine Tort Law. -Thus, under this framework, a quasi-delict is a kind of tort. In other words, a quasi-delict is a subset of tort and hence, every quasi-delict is a tort. But certainly every tort is a quasi delict c. Definition of Tort Under Philippine Law Naguiat v. NLRC G.R. No. 116123, March 13, 1997 -

“Essentially, ‘tort’ consists in the violation of a right given or the omission of a duty imposed by law. Simply stated, tort is

-

a breach of legal duty.” Consists in the violation of a right given or the omission of a

-

duty imposed by law. A breach of legal Duty

Vinzons-Chato v. Fortune G.R. No. 141309, June 19, 2007 -

“a tort is a Wrong” A tortuous act is the commission or omission of an act by one, without right, whereby another receives some injury,

-

directly or indirectly, in person, property or reputation. Court is saying that “intent is not an element of tort”

d. Elements of Tort According to Posser and Keeton, elements of torts are: 1. Duty or obligation recognized by law 2. Failure on the person’s part to conform to the standard: a breach of duty 3. Reasonably close causal connection between the conduct and resulting injury 4. Actual loss or damage resulting to the interest of others

Garcia v. Salvador G.R. No. 168512, March 20, 2007 Elements: 1. 2. 3. 4.

Duty Breach Injury Proximate Cause

Case: “The Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Test.” Mali yung result ng test ni Garcia. -The court ruled that “violation of a statutory duty is negligence. Where the law imposes upon a person the duty to do something, his omission or nonperformance will render him liable to whoever may be injured thereby.” - Garcia failed to comply with the standards because he conducted the test without the supervision of the pathologist and released the result without authorization of the latter. Lucas v. Tuaño, G.R. No. 178763, April 21 2009 Case: Yung nag ka sore eyes tapos nabulag ang isang mata ni Lucas. -

For lack of a specific law geared towards the type of negligence committed by of the medical profession, such claim for damages is almost always anchored on the alleged violation of Article 2176 of the Civil Code. In medical negligence cases, also called medical malpractice suits, there exist a physician-patient relationship between the doctor and the victim. But just like any other proceeding for damages, four essential (4) elements i.e., (1) duty; (2) breach; (3) injury; and (4) proximate causation,[76] must be established by the plaintiff/s. All the four (4) elements must co-exist in order

-

to find the physician negligent and, thus, liable for damages. There is breach of duty of care, skill and diligence, or the improper performance of such duty, by the attending physician when the patient is injured in body or in health [and this] constitutes the actionable malpractice. [80] Proof of such breach must likewise rest upon the testimony of an expert witness that the treatment accorded to the patient failed to meet the standard level of care, skill and diligence which physicians in the same general neighborhood and in the same general line of practice ordinarily possess and

-

exercise in like cases. Even so, proof of breach of duty on the part of the attending physician is insufficient, for there must be a causal connection between said breach and the resulting injury sustained by the patient. Put in another way, in order that there may be a recovery for an injury, it must be shown that the “injury

for which recovery is sought must be the legitimate consequence of the wrong done; the connection between the negligence and the injury must be a direct and natural sequence of events, unbroken by intervening efficient causes”; [81] that is, the negligence must be the proximate cause of the injury. And the proximate cause of an injury is that cause, which, in the natural and continuous sequence, unbroken by any efficient intervening cause, produces -

the injury, and without which the result would not have occurred.[82] Just as with the elements of duty and breach of the same, in order to establish the proximate cause [of the injury] by a preponderance of the evidence in a medical malpractice action, [the patient] must similarly use expert testimony, because the question of whether the alleged professional negligence caused [the patient’s] injury is generally one for specialized expert knowledge beyond the ken of the average layperson; using the specialized knowledge and training of his field, the expert’s role is to present to the [court] a realistic assessment of the likelihood that [the physician’s] alleged negligence caused [the patient’s] injury.

Ocean Builders v. Spouses Cubacub, G.R. No. 150898, April 13, 2011 (see Bersamin dissent) Case: “The chicken pox Incident” -

The court ruled that Hao (General Manager) was not negligent for he complied

-

with his obligation under article 161 of the Labor Code. This is interesting because negligence does not appear to be relevant in the context if the elements identified by the court nor in the violation of the legal

-

provision Regardless of whether the provision was violated negligently or not, the violations would be liable for damages. Negligence of the employer would only be relevant if the action was based on quasi-delict.

3. The Purpose of Tort Law -

Main purpose: Lesson/Exemplary/Deterrent Never would commit negligence again A form of example. Promote efficacy Purpose of tort law is compensation of individuals for losses which they have suffered within the scope of their legally recognized

-

interests. Providing compensation for harm Serves corrective justice Provide deterrent to harmful conduct

B. The Concept of Quasi-Delict 1. Historical Background Barredo v. Garcia G.R. No. 48006, July 8, 1942 -

Authorities the proposition that a quasi-delict or culpa-aquiliana is a separate legal institution under the civil code with a substantivity all its own, and individuality that

-

is entirely apart from a delict or crime. As interpreted by the code commission, the term “quasidelict” corresponds to what is referred to in Spanish legal treaties as “culpa-aquiliana,” “cupla-extra-contractual”, or “cuasi-delitos”.

2. Nature Articles 1157 (cf. 1089 old Code) Obligation arise from: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

Law Contracts Quasi-contracts Acts or omissions punished by law; and Quasi-delicts

Thus, a quasi-delict is one of the five sources of obligation. Article 1157 was derived from article 1089 of the old civil code. 3. Governing Provisions Article 1162

4. Definition

-

Quasi-delicts are primarily governed by 19 articles of the civil code

-

and by special laws. 19 articles of the civil code (Arts. 2176-2194)

Article 2176 Civil Code (cf 1902 old Code) -

Defines a quasi-delict as the fault or negligence that accompanies an act or omission which causes damage to

another, there being no pre-existing contractual relation between the parties. 5. Scope a. “Intentional” acts Article 2176 Cangco v. Manila Railroad, G.R. No. 12191. October 14, 1918 -

“the liability arising from extra-contractual culpa is always based upon a voluntary act or omission which, without willful intent, but by mere negligence or inattention, has

-

caused damage to another.” (Cangco vs Manila Railroad) A “voluntary act”- merely referring to an act freely done or

-

without compulsion. “Willful intent”- an act done for the purpose of harm.

Elcano v. Hill G.R. No. L-24803, May 26, 1977 -

Concept of Culpa aquiliana includes acts which are criminal in character or in violation of the penal law, which voluntary

-

or not. “the occurrence of the penal code and the civil code therein referred to contemplate only acts of negligence and not

-

intentional voluntary acts”. Quasi-delicts can cover acts committed through criminal

-

negligence “The nature of culpa aquiliana in relation to culpa criminal or delict and mere culpa or fault with pertinent citation of dicisions of the sc of spain, the works of recognized civilians, and earlier jurisprudence of our own that the same given act can result in civil liability not only under the penal code but

-

also under the civil code.”

Andano v. IAC G.R. No. 74761, November 6, 1990 -

Art 2176, whenever it refers to fault or negligence covers not only acts “not punishable by law” but also acts criminal in character, whether intentional and voluntary or negligent.

-

Court agreed with andamos that civil action was based on a quasi-delict.

Baksh v. CA G.R. No. 97336. February 19, 1993. -

The court ruled that quasi-delict “is limited to negligent acts or omissions and excludes the notion of willfulness or

-

intent” Torts is much broader that culpa-aquiliana because it includes not only negligence, but intentional criminal acts as well as such assaults and battery, false imprisonment and

-

deceit. Thus, the court explained that art 2176 only covered negligent acts and omissions on the basis og the “general scheme of the Philippine Legal system envisioned by the

-

[code] commissioners. A quasi-delict is committed by negligence and without willful intent to be voluntary and negligent at the same time, but it cannot be “intentional” in the sense that there is intent to harm and negligent at the same time.

b. Damage to Property Cinco v. Canonoy G.R. No. L-33171, May 31, 1979 -

Quasi-delict is so broad that it includes not only injuries to

-

persons but also damage to property. It makes no distinction between “damage to persons” on the one hand and “damage to property” on the other. Indeed, the word “damage” is used in two concepts: the harm done and reparation for the harm done. And with respect to “harm” is not limited to personal but also to property injuries.

6. Elements Article 2176 1. Act or Omission 2. Damage to another 3. Fault or negligence; and 4. No pre-existing contractual relation

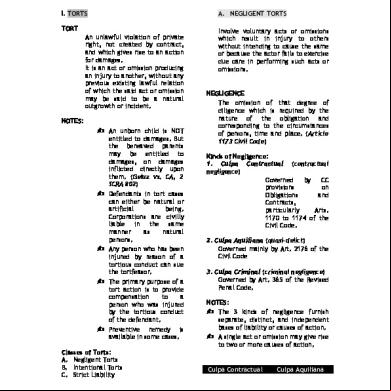

Andamo v. IAC G.R. No. 74751 November 6, 1990 1. Damage to the plaintiff 2. Negligence by act or omission of the defendant, or by some other person for whose act the defendant must respond; and 3. Connection of cause and effect between the fault or negligence of the defendant and the damage incurred by the plaintiff. C. The Relationship Between Tort and Quasi- Delict 1. Distinct concepts -Torts under Philippine law are those causes of action entitling a person to remedies, mainly in the form of damages, for the injury caused to him. -A quasi-delict is the concept dfined under article 1276 of the Civil Code. It is a cause of action whereby one who is injured by an act or omission of another, there being fault or negligence, is entitled to an award of damages, there being no preexisting contractual relationship between the parties - Torts: A classification of several causes of action. It includes both negligence acts and acts with intent to harm. -Quasi-delict: Is a single cause of action. Cover only negligent acts with no intent to harm 2. Framework -One way of looking is that a quasi-delict is a tort committed via negligence or a quasi delict is a “negligence tort”. - The Relationship may be represented by two circles, with quasi-delict as smaller circle completely within the larger circle of tort. D. Quasi- Delict & Delict 1. Distinguishing quasi- delict & delict - Whatever happens to the criminal action does not affect the quasi-delictual action. The success of the quasi-delictual action does not depend on the success of the criminal action. Barredo v. Garcia, G.R. No. 48006, 8 July 1942 -

Difference between crimes and cuasi-delitos 1. That the crimes affect the PUBLIC INTEREST, while cuasi-delitos are only of private concern

2. That, consequently , the Penal Code punishes or corrects the criminal act, while the civil code, by means of indemnification, merely repairs the damage. 3. That delicts are not as broad as quasi-delicts, because the former are punished only if there is a penal law clearly covering them, while the latter, cuasi-delitos, include all acts in which “any kind of fault or negligence intervenes.” 2. Overlap between quasi- delict & delict Barredo v. Garcia, supra - If we were to hold that articles 1902 to 1910 of the Civil Code refer only to fault or negligence not punished by law, according to the literal import of article 1093 of the Civil Code, the legal institution of culpa -

aquiliana would have very little scope and application in actual life. To find the accused guilty in a criminal case, proof of guilt beyond reasonable doubt is required, while in a civil case, preponderance of

-

evidence is sufficient to make the defendant pay in damages. To hold that there is only one way to make defendant's liability effective, and that is, to sue the driver and exhaust his (the latter's) property first, would be tantamount to compelling the plaintiff to follow a devious and cumbersome method of obtaining relief.

Elcano v. Hill, supra -

-

“Under the proposed Article 2177, acquittal from an accusation of criminal negligence, whether on reasonable doubt or not, shall not be a bar to a subsequent civil action, not for civil liability arising from criminal negligence, but for damages due to a quasi-delict or 'culpa aquiliana'. But said article forestalls a double recovery." Art 2177 further s the view that the same act, which was the basis of a criminal action can be the basis for a civil action for damages.

Andamo v. IAC, supra - In the case of Castillo vs. Court of Appeals, 15 this Court held that a quasidelict or culpa aquiliana is a separate legal institution under the Civil Code with a substantivity all its own, and individuality that is entirely apart and independent from a delict or crime — a distinction exists between the civil liability arising from a crime and the responsibility for quasi-delicts or culpa extra-contractual. The same negligence causing damages may produce civil liability arising from a crime under the Penal Code, or create an action for

quasi-delicts or culpa extra-contractual under the Civil Code. Therefore, the acquittal or conviction in the criminal case is entirely irrelevant in the civil case, unless, of course, in the event of an acquittal where the court has declared that the fact from which the civil action arose did not exist, in which case the extinction of the criminal liability would carry with it the extinction of the civil liability. L.G. Foods v. Philadelfa G.R. no. 158995. September 26, 2006 - An act or omission causing damage to another may give rise to two separate civil liabilities on the part of the offender, 1) civil liability ex delicto; and 2) independent civil liabilities, such as those (a) not arising from an act or omission complained of as felony (e.g., culpa contractual or obligations arising from law; the intentional torts; and culpa aquiliana); or (b) where the injured party is granted a right to file an action independent and distinct from the criminal action. Either of these two possible liabilities may be enforced against the offender. - the court ruled that the case was a negligence suit brought under article 2176 of the civil code to recover damages primarily from the petitioners as employers responsible for their negligent driver pursuant to article 2180 of the civil code.

E. Culpa aquiliana and Culpa contractual 1. Distinguishing culpa aquiliana from culpa contractual Non-contractual Obligation- It is the wrongful or negligent act or omission itself which creates the Vinculum Juris. Contractual Relations- the Vinculum exists independently of the breach of the voluntary duty assumed by the parties when entering into the contractual relation. Extraordinary Diligence- Diligence as far as human care and foresight can provide. Diligence of a good father = Diligence of a reasonable man

a. Source Cangco v. Manila Railroad, supra - Foundation of the legal liability of Manila Railroad was the contract of carriage, and that the obligation to respond for the damage which Cangco had suffered arose from the Breach of that contract by reason of the failure of Manila Railroad to exercise Due care in its performance.

b. Burden of proof Negligent act or omission (culpa aquillana) -

The burden of proof rests upon plaintiff to prove the

-

negligence. Negligence or the fault

Contractual undertaking (culpa contractual) -

Proof of the contract and its non-performance is sufficient

-

prima facie to warrant a recovery. All that the plaintiff had to present were proof of the contract and its non-performance.

Cangco v. Manila Railroad, supra FGU Insurance v. Sarmiento G.R. No. 141910 August 6, 2002 - The mere proof of the existence of the contract and the failure of its compliance justify, prima facie, a corresponding right of relief. The kaw, recognizing the obligatory force of contracts, will not permit a partyto be set free from liability for any kind of misperformance of the contractual -

undertaking or a contravention of the tenor thereof. Unless he can show extenuating circumstances, like proof of his exercise of due diligence or of the attendance of furtuitos event, to excuse him from his ensuing liability.

c. Applicability of doctrine of proximate cause Calalas v. CA G.R. No. 122039, 31 May 2000.

-

The doctrine of proximate cause is applicable only in actions for quasi-delict, not in actions involving breach of contract. The doctrine is a device for imputing liability to a person where there is no relation between him and another party. In such a case, the obligation is created by law itself. But, where there is a pre-existing contractual relation between the parties, it is the parties themselves who create the obligation, and the function of the law is merely to regulate the relation thus created.

d. Defense of Employer for Negligence of Employee -A case of culpa aquillana, then the employer can be held liable on the basis of his own negligene. - A proof of the employer’s negligence is not required in culpa contractual. The employer cannot raise the defense that the breach was caused by te negligence of his employees. 2. Is there an Intersection? Article 2176 Cangco v. Manila Railroad, supra Fores v. Miranda, G.R. No. L-12163, March 4, 1959 - Definition of quasi delict expressly excludes the cases where there is a “pre-existing contractual relation between parties.” Consolidated Bank v. CA G.R. No. 138569, September 11, 2003 - The Law on Quasi-delict or culpa aquilliana is generally applicable when there is no pre-existing contractual -

relationship between the parties. As a general rule, a quasi-delict cannot exist if there is a pre-

existing contractual relationship between the parties. Air v. Carrascoso G.R. No. L-21438, September 28, 1966 - Although the relation of enger and carrier is “contractual both in origin and nature” nevertheless “the act -

that breaks the contract may also be a tort” The contract of air carriage generates a relation attended with public duty. Neglect or malfeasance of the carrier’s employees, naturally, could give ground for an action for damages.

-

engers do not contract merely for transportation… So it is, that any rude or discourteous conduct on the part of employees towards a enger gives the latter an action for

damages against the carrier. Far East v. CA G.R. No. 108164, February 23, 1995 - Where, without a preexisting contract between two parties, an act or omission can nonetheless amount to an actionable tort by itself, the fact that the parties are contractually bound is no bar to the application of quasi-delict provisions -

to the case. Thus under this test, the second sentence of art. 2176 is interpreted not as a rule of preclusion (i.e. the existence of a contract precludes the existence of a quasidelict) but merely a rule requiring independence. This means that a quasi0delict can exisit between contractual parties if the case of action exists without a contract.

PSBA v. CA G.R. No.. 84698, February 4, 1992 - When an academic institution accepts students for enrollment, there is established a contract between them, resulting in bilateral obligations which both are bound to comply with. For its part, the school undertakes to provide the students with an education that would presumably suffice to equip him with necessary tools and skills to pursue higher education or a profession. On the other hand, the student’s covenants to abide by the school’s academic -

requirements and observe its rule and regulations. In the circumstances obtaining in the case at bar, however, there is, as yet, no finding that the contract between the school and Bautista had been breached thru the former's negligence in providing proper security measures. This would be for the trial court to determine. And, even if there be a finding of negligence, the same could give rise generally to a breach of contractual obligation only. Using the test of Cangco, supra, the negligence of the school would not be relevant absent a contract. In fact, that negligence becomes material only because of the contractual relation between PSBA and Bautista. In other words, a contractual relation is

a condition sine qua nonto the school's liability. The negligence of the school cannot exist independently of the contract, unless the negligence occurs under the circumstances set out in Article 21 of the Civil Code. Syquia v. CA G.R. No. 98695, January 27, 1993 - A pre-existing contractual relation between the parties does not preclude the existence of a culpa aquiliana. Light Rail Transit v. Navidad, G.R. No. 145804. February 6, 2003 - liability for tort may arise even under a contract, where tort is that which breaches the contract. Stated differently, when an act which constitutes a breach of contract would have itself constituted the source of a quasi-delictual liability had no contract existed between the parties, the contract can be said to have been breached by tort, thereby allowing the rules on tort to apply. II.

NEGLIGENCE

A. Concept of Negligence Article 1173 - Article 1173. The fault or negligence of the obligor consists in the omission of that diligence which is required by the nature of the obligation and corresponds with the circumstances of the persons, of the time and of the place. When negligence shows bad faith, the provisions of Articles 1171 and 2201, paragraph 2, shall apply. If the law or contract does not state the diligence which is to be observed in the performance, that which is expected of a good father of a family shall be required. Article 2178. The provisions of Articles 1172 to 1174 are also applicable to a quasi-delict. 1. Determining the diligence required Article 1173

-

Determining the diligence required Article 1173. The fault or negligence of the obligor consists in the omission of that diligence which is required by the nature of the obligation and corresponds with the circumstances of the persons, of

-

the time and of the place. When negligence shows bad faith, the provisions of Articles 1171 and 2201, paragraph 2, shall apply. What determines the diligence required are the following: 1. The nature of the obligation; and 2. The circumstances of the persons, of the time and of the place.

Jorge v. Sicam G.R. No. 159617, August 8, 2007 - The diligence with which the law requires the individual at all times to govern his conduct varies with the nature of the situation in which he is placed and the importance of the act which he is to perform. Far Eastern Shipping v. CA, G.R. No. 130068. October 1, 1998 - Generally, the degree of care required is graduated according to the danger a person or property attendant upon the activity which the actor pursues or the instrumentality which he uses. The greater the danger the greater the degree of care required. What is ordinary under extraordinary of conditions is dictated by those conditions; extraordinary risk demands extraordinary care. Similarly, the more imminent the danger, the higher the degree of care. PNR v. Brunty, G.R. No. 169891. November 2, 2006 - A collision occurred between a car and a PNR train at 12 AM causing the death of Brunty, a enger of the car. The car was overtaking another car, with a blind curve ahead, when it hit the train. PNR was found negligent. - Doctrine: Negligence is the omission to do something which a reasonable man, guided by those considerations which ordinarily regulate the conduct of human affairs, would do, or the doing of something which a prudent and reasonable man would not do. The test is, did the defendant, in doing the alleged negligent act, use that reasonable care and caution which an ordinarily prudent person would have used in the same situation? If not, the person is guilty of negligence. The law, in effect, adopts the standard supposed to be supplied by the imaginary conduct of the discreet pater familias of the Roman law. - Notes: The negligence of PNR consists in the inadequate safety precautions placed in the site. The extraordinary diligence required of common carriers is not applicable in this case since Brunty was not a enger.

PNR v. CA. G.R. No. 157658, 15 October 2007 - Amores was driving when he came toa railroad crossing. He stopped before crossing then proceeded. But just as he was at the intersection, a PNR train turned up and collided with his car, killing him. There was neither a signal nor a crossing bar at the intersection to warn motorists and aside from the railroad track, the only visible warning sign was a dilapidated "stop, look, and listen" sign. No whistle blow was heard from the train before the collision. The SC held PNR liable, and that Amores did everything, with absolute care and caution, to avoid the collission. - Doctrine: Negligence has been defined as ‘the failure to observe for the protection of the interests of another person that degree of care, precaution, and vigilance which the circumstances justly demand, whereby such other person suffers injury. 2. Default standard of diligence Article 1173

-

If the law or contract does not state the diligence which is to be observed in the performance, that which is expected of a good father of a family shall be required.

B. Degrees of Negligence Amedo v. Rio G.R. No. L-6870, May 24, 1954 - Managuit was a seaman. While he was on board the ship doing his job, he jumped into the water to retrieve his 2-peso bill, which was blown by the wind. He drowned. His mother was not allowed to recover because in acting as such, he was grossly negligent. Doctrine: Gross negligence is defined to be the want of even slight care and diligence. By gross negligence is meant such entire want of care as to raise a presumption that the person in fault is conscious of the probable consequences of carelessness, and is indifferent, or worse, to the danger of injury to person or property of others. It amounts to a reckless disregard of the safety of person or property. - Notes: When the act is dangerous per se, doing it constitutes -

gross negligence. To compensate his employer for a personal injry: 1. Arise out of employment

2. In the course of employment 3. Not caused by notorious negligence/gross negligence. Marinduque v. Workmen’s G.R. No. L-8110, June 30, 1956 - Mamador was laborer. He boarded a company truck with others to go to work. When it tried to overtake another truck, it turned over and hit a coconut tree. Mamador died. Upon complaint, the defense of the company was that Mamador was notoriously negligent, for violating a company policy prohibiting riding in hauling trucks, and was, thus, barred from recovery. The SC cited Corpus Juris to the effect that violation of a rule promulgated by a commission or board is not negligence per se, much less that of a company policy. It may, however, evidence negligence. Even granting that there was negligence, it certainly was not notorious. - Doctrine: Notorious negligence is the same as gross negligence, which implies a conscious indifference to consequences, pursuing a course of conduct which would naturally and probably result in injury, or utter disregard of consequences. Notes: Mere riding or stealing a ride on a hauling truck is not negligence, ordinarily, because transportation by truck is not dangerous per se. Ilao- Oreta v. Ronquillo G.R. No. 172406, October 11, 2007 - Dr. Ilao-Oreta failed to attend to a scheduled laparoscopic operation scheduled by the spouses Ronquillo, to determine the cause of the wife's infertility. The wife already underwent pre-operation procedures at that time. Dr. Ila-Oreta claimed that she was in good faith, only failing to the time difference between the Philippines and Hawaii, where she had her honeymoon. The SC ruled that her conduct was not grossly negligent, since the operation was only exploratory. Her "honeymoon excitement" was also considered. Doctrine: Gross negligence is the want or absence of or failure to exercise slight care or diligence or the entire absence of care. Notes: That she failed to consider the time difference was probably a big lie, since the estimated time of arrival is clearly shown in the ticket. C. Standard of conduct 1. Importance of a Standard of Conduct

-

Reasonable man changes every time. It leave us to compare the standard conduct

2. The Fictitious Person a. Common law’s reasonable person b. Civil law’s “good father of a family” TEST: 1. Did the defendant in doing the alleged negligent act use that reasonable care and caution which an ordinarily prudent person would have used in the same situation? If not then he is guilty of negligence. 2. Whether the actor disregarded the foreseeable harm caused by his action. Article 1173 Picart v. Smith G.R. No. L-12219, March 15, 1918 - An automobile hit a horseman, who was on the wrong side of the road. The horseman thought he did not have time to get to the other side. The car ed by too close that the horse turned its body across, with its head toward the railing. Its limb was broken, and its rider was thrown off and injured. The SC found the automobile driver negligent, since a prudent man should have foreseen the risk in his course and that he had the last fair chance to avoid the harm. Doctrine: The test to determine the existence of negligence in a particular case is: Did the defendant in doing the alleged negligent act use that reasonable care and caution which an ordinarily prudent person would have used in the same situation? The law here in effect adopts the standard suppose to be supplied by the imaginary conduct of the discreet paterfamilias of the Roman law. The existence of negligence in a given case is not determined by reference to the personal judgment of the actor in the situation before him. The law considers what would be reckless, blameworthy, or negligent in the man of ordinary intelligence and prudence and determines liability by that. Notes: The Picart test is the most cited test of negligence. It introduced the use of the fictitious person. It has the markings of common law but because it uses the concept of

the discreet paterfamilias, later enshrined in the Civil Code as the good father of a family, it is now a civil law test. Sicam v. Jorge G.R. No. 159617. August 8, 2007 - Jorge pawned jewelry with Agencia de R. C. Sicam. Armed men entered the pawnshop and took away cash and jewelry from the pawnshop vault. Jorge demanded the return of the jewelry. The pawnshop failed. The SC held Sicam liable for failing to employ sufficient safeguards for the pawned goods. It held that robbery, if negligence concurred, is not a fortuitous event. Also, Article 2099 requires a creditor to take care of the thing pledged with the diligence of a good father of a family. Doctrine: The diligence with which the law requires the individual at all times to govern his conduct varies with the nature of the situation in which he is placed and the importance of the act which he is to perform. Negligence, therefore, is the omission to do something which a reasonable man, guided by those considerations which ordinarily regulate the conduct of human affairs, would do; or the doing of something which a prudent and reasonable man would not do. It is want of care required by the circumstances. Notes: The fictitious person is not the standard. It is his conduct. Corinthian Gardens v. spouses Tanjangco G.R. No. 160795. June 27, 2008 - The Cuasos built their house on a lot ading that owned by the Tanjangcos. Their plan was approved by Corinthian Gardens. It turned out, however, that the house built encroached on the lot of the Tanjangcos. The SC found Corinthian Gardens negligent for conducting only "table inspections," when it should have conducted actual site inspections, which could have prevented the encroachment. Doctrine: A negligent act is an inadvertent act; it may be merely carelessly done from a lack of ordinary prudence and may be one which creates a situation involving an unreasonable risk to another because of the expectable action of the other, a third person, an animal, or a force of nature. A negligent act is one from which an ordinary prudent person in the actor's position, in the same or similar circumstances, would foresee such an appreciable risk of harm to others as to cause him not to do the act or to do it in a more careful manner. Notes: The test cited in the case was the Picart test.

3. Special Circumstances Añonuevo v. CA G.R. No. 130003 20 October 2004

- There long has been judicial recognition of the peculiar dangers posed by the motor vehicle. As far back as 1912, in the U.S. v. Juanillo25, the Court has recognized that an automobile is capable of great speed, greater than that of ordinary vehicles hauled by animals, "and beyond doubt it is highly dangerous when used on country roads, putting to great hazard the safety and lives of the mass of the people who travel on such roads."26 In the same case, the Court emphasized: A driver of an automobile, under such circumstances, is required to use a greater degree of care than drivers of animals, for the reason that the machine is capable of greater destruction, and furthermore, it is absolutely under the power and control of the driver; whereas, a horse or other animal can and does to some extent aid in averting an accident. It is not pleasant to be obliged to slow down automobiles to accommodate persons riding, driving, or walking. It is probably more agreeable to send the machine along and let the horse or person get out of the way in the best manner possible; but it is well to understand, if this course is adopted and an accident occurs, that the automobile driver will be called upon to for his acts. An automobile driver must at all times use all the care and caution which a careful and prudent driver would have exercised under the circumstances. Heirs of Completo v. Albayda G.R. No. 172200. July 6, 2010 - Albayda, Master Sergeant in the Philippine Air Force, was at an intersection riding his bike when he was hit by a taxi driven by Completo. Albayda suffered injuries, including breaking his knee. The SC found Completo negligent, since he was overspeeding when he reached the intersection. Also, the bike already had the right of way at the time of the incident. Doctrine: The bicycle occupies a legal position that is at least equal to that of other vehicles lawfully on the highway, and it is fortified by the fact that usually more will be required of a motorist than a bicyclist in discharging his duty of care to the other because of the physical advantages the automobile has over the bicycle. Notes: The witnesses for the same parties are of the same number. It seems odd, therefore, to apply the test of negligence when the facts are not settled by preponderance

of evidence. Thus, it appears that the court sympathized with Albayda, who was serving the government and was left by his wife, supposedly because of his injuries. Pacis v. Morales G.R. No. 169467. February 25, 2010 - Morales owned a gun shop. An employee of the shop allowed Pacis to inspect a gun brought in for repair. It turned out that the gun was loaded and when Pacis laid it down, it discharged a bullet, hitting his head. He died. The SC found Morales, as the owner, liable, since he failed to exercise the diligence required of a good father of a family, much less that required of someone dealing with dangerous weapons. - Doctrine: A higher degree of care is required of someone who has in his possession or under his control an instrumentality extremely dangerous in character, such as dangerous weapons or substances. Such person in possession or control of dangerous instrumentalities has the duty to take exceptional precautions to prevent any injury being done thereby. Unlike the ordinary affairs of life or business which involve little or no risk, a business dealing with dangerous weapons requires the exercise of a higher degree of care. - Notes: Two things may be considered negligent: the keeping of a defective gun loaded and the storing a defective gun in a drawer. It is strange, however, that the negligence of the employee was not discussed, when the presumption that the employer was negligent only arises after the negligence of the employee is established. Also, that the wound sustained was in the head appears to be a factual anomaly. 4. Children Taylor v. Manila Railroad G.R. No. 4977 March 22, 1910 - David Taylor, 15 years old, and Manuel, 12, obtained fulminating caps from the compound of Manila Railroad. They experimented on them. The experiment ended with a bang, literally. The explosion caused injury to the right eye of Taylor. His father sued for damages. The defense of Manila Railroad is the entry to their compound was without its invitation. The SC held that the absence of invitation cannot relieve Manila Railroad from liability. However, it held that the proximate cause of the injury was Taylor's negligence.

Doctrine: The personal circumstances of the child may be considered in determining the existence of negligence on his part. Notes: The age-bracket regime, where certain age groups are treated as incapable of negligent conduct, was not applied here. Also, the standard applied differs from that objective standard of conduct generally applied to adults. Jarco Marketing v. CA G.R. No. 129792. December 21, 1999 - Zhieneth, 6 years old, was pinned down by a gift-wrapping counter at a department store, when her mother momentarily let her go to sign a credit card slip. She died. The SC found Jarco Marketing negligent, since it did not employ safety measures even when it knew that the counter was unstable. That Zhieneth was negligent, that she climbed the counter, is incredible. Doctrine: A conclusive presumption runs in favor of children below 9 years old that they are incapable of contributory negligence. Notes: The 9-year mark was adopted from the Sangco's discussion on the matter, citing the same age mark for determining discernment in criminal law. This analogy, however, is erroneous since discernment, in criminal law, is used to determine the existence of criminal intent, which is wildly different from negligence. Ylarde v. Aquino G.R. No. L-33722. July 29, 1988 - Ylarde, a 10-year old student, and other fellow students were asked by Aquino, their teacher, to help him in burying large blocks of stones. Aquino left them for a while and told them not to touch anything. After Aquino left, they played and Ylarde jumped into the hole while one of them jumped on the stone, causing it to slide into the hole. Ylarde was not able to get out of the hole in time and died. The SC ruled that Aquino was negligent in leaving his pupils in the dangerous site, and that it was natural for said pupils to play. It disregarded the claim that Ylarde was imprudent. Doctrine: The degree of care required to be exercised must vary with the capacity of the person endangered to care for himself. A minor should not be held to the same degree of care as an adult, but his conduct should be judged according to the average conduct of persons of his age and experience. The standard of conduct to which a child must

conform for his own protection is that degree of care ordinarily exercised by children of the same age, capacity, discretion, knowledge and experience under the same or similar circumstances. Notes: The choice of standard of diligence for children also depends on the facts and circumstances of the case.

5. Experts a. In general -Standards= Higher than a prudent man

Far Eastern Shipping v. CA, G.R. No. 130068. October 1, 1998. - Those who undertake any work calling for special skills are required not only to exercise reasonable care in what they do but also possess a standard minimum of special knowledge and ability. Every man who offers his services to another, and is employed, assumes to exercise in the employment such skills he possesses, with a reasonable degree of diligence. In all these employments where peculiar skill is requisite, if one offers his services he is understood as holding himself out to the public as possessing the degree of skill commonly possessed by others in the same employment, and if his pretensions are unfounded he commits a species of fraud on every man who employs him in reliance on his public profession.

Culion v. Phiippine Motors G.R. No. 32611. November 3, 1930 - Culion contracted Philippine Motors to convert the engine of his fishing vessel to process crude oil instead of gasoline. When they tried to test it, a backfire broke out. When it reached the carburetor, the fire grew bigger. Apparently, the carburetor was soaked with oil from a leak from the tubing, which was improperly fitted to the oil tank. The SC held Philippine Motor negligent for failing to use the skill that would have been exhibited by one ordinarily expert in repairing gasoline engines on boats. Ordinarily, a backfire would not be followed by a disaster. - Doctrine: When a person hold himself out as being competent to do things requiring professional skill, he will be liable for negligence if he fails to exhibit the care and skill of one ordinarily skilled in the particular work which he attempts to do.

b. Pharmacist US v. Pineda G.R. No. L-12858. January 22, 1918 - Santos bought medicine in Santiago Pineda’s pharmacy for his sick horses. He was given the wrong medicine. His horses died. The SC held him criminally liable under The Pharmacy Law. Doctrine: The profession of pharmacy is one demanding care and skill. The responsibility of the druggist to use care has been variously qualified as "ordinary care," "care of a specially high degree," "the highest degree of care known to practical men." In other words, the care required must be commensurate with the danger involved, and the skill employed must correspond with the superior knowledge of the business which the law demands. Caveat emptor does not apply because the pharmacist and the customer are not in equal footing in this kind of transaction. Notes: Even when the mistake is not fatal, the pharmacist will still be held liable if the rule laid down applied. Also, caveat emptor may apply in cases of well-known medicine. Mercury Drug v. De Leon G.R. No. 165622. October 17, 2008 - Judge De Leon was given a prescription by his doctor friend for his eye. He bought them from Mercury Drug but he was given drops for the ears. When he applied the drops to his eyes, he felt searing pain. Only then did he discover that he was given the wrong medicine. Mercury Drug invoked the principle of caveat emptor. The SC held Mercury Drug and its employee liable for failing to exercise the highest degree of diligence expected of them. - Doctrine: The profession of pharmacy demands care and skill, and druggists must exercise care of a specially high degree, the highest degree of care known to practical men. In other words, druggists must exercise the highest practicable degree of prudence and vigilance, and the most exact and reliable safeguards consistent with the reasonable conduct of the business, so that human life may not constantly be exposed to the danger flowing from the substitution of deadly poisons for harmless medicines. c. Medical professionals NOTE: Witnesses must of the same specific specialization

The elements of medical negligence are: (1) duty; (2) breach; (3) injury; and (4) proximate causation. Cruz v. CA G.R. No. 1224-15. November 18, 1997 - Dr. Cruz performed a hysterectomy on Lydia Umali. The hospital was untidy, and during the operation, the family had to obtain blood, oxygen supply, and other articles necessary for the operation outside the hospital. Lydia went into shock and her blood pressure dropped. She was transferred to another hospital. Dr. Cruz was charged with reckless imprudence resulting to homicide. The SC absolved Dr. Cruz. While the facts point to the existence of reckless imprudence, it was not shown that such imprudence caused the death of Lydia. Moral and exemplary damages were, however, awarded. Doctrine: By accepting a case, a doctor in effect represents that, having the needed training and skill possessed by physicians and surgeons practicing in the same field, he will employ such training, care and skill in the treatment of his patients. He therefore has a duty to use at least the same level of care that any other reasonably competent doctor would use to treat a condition under the same circumstances. It is in this aspect of medical malpractice that expert testimony is essential to establish not only the standard of care of the profession but also that the physician's conduct in the treatment and care falls below such standard. Further, inasmuch as the causes of the injuries involved in malpractice actions are determinable only in the light of scientific knowledge, it has been recognized that expert testimony is usually necessary to the conclusion as to causation.

Dela Torre v. Imbuido G.R. No. 192973 September 29, 2014 -

"[M]edical malpractice or, more appropriately, medical negligence, is that type of claim which a victim has available to him or her to redress a wrong committed by a medical professionalwhich has caused bodily harm." In order to

successfully pursue such a claim, a patient, or his or her family as in this case, "must prove that a health care provider, in most cases a physician, either failed to do something which a reasonably prudent health care provider would have done, or that he or she did something that a reasonably prudent provider would not have done; and that failure or action caused injury to the patient." -

The Court emphasized in Lucas, et al. v. Tuaño that in medical negligence cases, there is a physician-patient relationship between the doctor and the victim, but just like in any other proceeding for damages, four essential elements must be established by the plaintiff, namely: (1) duty; (2) breach; (3) injury; and (4) proximate causation. All four elements must be present in order to find the physician negligent and, thus, liable for damages.

-

Note: The critical and clinching factor in a medical negligence case is proof of the causal connection between the negligence and the injuries.

Casumpang v. Cortejo G.R. Nos.171127, 171217 & 171221 March 11, 2015 -

Once a physician-patient relationship is established, the legal duty of care follows. The doctor accordingly becomes duty-bound to use at least the same standard of care that a reasonably competent doctor would use to treat a medical condition under similar circumstances.

-

Medical malpractice suit, an action available to victims to redress a wrong committed by medical professionals who caused bodily harm to, or the death of, a patient.33 As the term is used, the suit is brought whenever a medical practitioner or health care provider fails to meet the standards demanded by his profession, or deviates from this standard, and causes injury to the patient.

-

To successfully pursue a medical malpractice suit, the plaintiff (in this case, the deceased patient’s heir) must prove

that the doctor either failed to do what a reasonably prudent doctor would have done, or did what a reasonably prudent doctor would not have done; and the act or omission had caused injury to the patient.34 The patient’s heir/s bears the burden of proving his/her cause of action. Borromeo v. Family Care Hospital, Inc. G.R. No. 191018 January 25, 2016 - The standard is based on the norm observed by other reasonably

-

III.

competent of the profession practicing the same field of medicine. Because medical malpractice cases are often highly technical, expert testimony is usually essential to establish: (1) the standard of care that the defendant was bound to observe under the circumstances; (2) that the defendant's conduct fell below the acceptable standard; and (3) that the defendant's failure to observe the industry standard caused injury to his patient. The expert witness must be a similarly trained and experienced physician. Thus, a pulmonologist is not qualified to testify as to the standard of care required of an anesthesiologist22 and an autopsy expert is not qualified to testify as a specialist in infectious diseases. PRESUMPTIONS OF NEGLIGENCE

A. In motor vehicle mishaps Article 2184. In motor vehicle mishaps, the owner is solidarily liable with his driver, if the former, who was in the vehicle, could have, by the use of due diligence, prevented the misfortune. It is disputably presumed that a driver was negligent, if he had been found guilty of reckless driving or violating traffic regulations at least twice within the next preceding two months. If the owner was not in the motor vehicle, the provisions of Article 2180 are applicable. Article 2185. Unless there is proof to the contrary, it is presumed that a person driving a motor vehicle has been negligent if at the time of the mishap, he was violating any traffic regulation. 1. Previous violation Articles 2184 2. Simultaneous violations

Article 2185 Tison v. Sps. Pomasin G.R. No. 173180 August 24, 2012 -

The court gave greater weight to the trial court’s finding of negligence on the part of the jitney driver and that this was the proximate cause of the accident.

-

We(SC) did not lose sight of the fact that at the time of the incident, Jabon was prohibited from driving the truck due to the restriction imposed on his driver’s license, i.e., restriction code 2 and 3. As a matter of fact, Jabon even asked the Land Transportation Office to reinstate his articulated license containing restriction code 8 which would allow him to drive a tractor-trailer. The Court of Appeals concluded therefrom that Jabon was violating a traffic regulation at the time of the collision.

-

Driving without a proper license is a violation of traffic regulation. Under Article 2185 of the Civil Code, the legal presumption of negligence arises if at the time of the mishap, a person was violating any traffic regulation. However, in Sanitary Steam Laundry, Inc. v. Court of Appeals,27 we held that a causal connection must exist between the injury received and the violation of the traffic regulation. It must be proven that the violation of the traffic regulation was the proximate or legal cause of the injury or that it substantially contributed thereto. Negligence, consisting in whole or in part, of violation of law, like any other negligence, is without legal consequence unless it is a contributing cause of the injury.

Sanitary Steam v. CA G.R. No. 119092 December 10, 1998 Doctrine: The violation if the traffic code was not enough. Such violation must be the proximate cause of the injury. It did not say that the

violation must be the proximate cause before the presumption could arise.

-

First of all, it has not been shown how the alleged negligence of the Cimarron driver contributed to the collision between the vehicles. Indeed, petitioner has the burden of showing a causal connection between the injury received and the violation of the Land Transportation and Traffic Code. He must show that the violation of the statute was the proximate or legal cause of the injury or that it substantially contributed thereto. Negligence, consisting in whole or in part, of violation of law, like any other negligence, is without legal consequence unless it is a contributing cause of the injury. 3 Petitioner says that "driving an overloaded vehicle with only one functioning headlight during nighttime certainly increases the risk of accident," 4 that because the Cimarron had only one headlight, there was "decreased visibility," and that the tact that the vehicle was overloaded and its front seat overcrowded "decreased [its] maneuverability," 5 However, mere allegations such as these are not sufficient to discharge its burden of proving clearly that such alleged negligence was the contributing cause of the injury.

Añonuevo v. CA G.R. No. 130003 20 October 2004 -

The Code Commission was cognizant of the difference in the natures and attached responsibilities of motorized and nonmotorized vehicles. Art. 2185 was not formulated to compel or ensure obeisance by all to traffic rules and regulations. If such were indeed the evil sought to be remedied or guarded against, then the framers of the Code would have expanded the provision to include non-motorized vehicles or for that matter, pedestrians. Yet, that was not the case; thus the need arises to ascertain the peculiarities attaching to a motorized vehicle within the dynamics of road travel. The fact that there has long existed a higher degree of diligence and care imposed on motorized vehicles, arising from the

special nature of motor vehicle, leads to the inescapable conclusion that the qualification under Article 2185 exists precisely to recognize such higher standard. Simply put, the standards applicable to motor vehicle are not on equal footing with other types of vehicles. Note: the court ruled that article 2185 should not apply to non-motorized vehicles, even by analogy. It said that there was factual and legal basis that necessitated the distinction under Article 2185, and to adopt Anonuevo’s thesis would unwisely obviate this distinction. B. Possessions of dangerous weapons or substance Article 2188 Article 2188. There is prima facie presumption of negligence on the part of the defendant if the death or injury results from his possession of dangerous weapons or substances, such as firearms and poison, except when the possession or use thereof is indispensable in his occupation or business. C. Common carriers Articles 1734-1735, 1752 Article 1734. Common carriers are responsible for the loss, destruction, or deterioration of the goods, unless the same is due to any of the following causes only: (1) Flood, storm, earthquake, lightning, or other natural disaster or calamity; (2) Act of the public enemy in war, whether international or civil; (3) Act or omission of the shipper or owner of the goods; (4) The character of the goods or defects in the packing or in the containers; (5) Order or act of competent public authority. Article 1735. In all cases other than those mentioned in Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 of the preceding article, if the goods are lost, destroyed or deteriorated, common carriers are presumed to have been at fault or to have acted negligently, unless they prove that they observed extraordinary diligence as required in Article 1733. D. Res ipsa loquitur 1. Definition 2. Statement of the Rule

Definition/statement of the rule. This doctrine is stated thus: “Where the thing which causes injury is shown to be under the management of the defendant, and the accident is such as in the ordinary course of things does not happen if those who have the management use proper care, it affords reasonable evidence, in the absence of an explanation by the defendant, that the accident arose from want of care.

3. Elements 1. Occurrence of an injury and it does not occur out of normal course of event, unless someone is negligent. 2. The thing which caused the injury was under control and management of the defendant (exclusive control) 3. The occurrence was such in the ordinary course of things would not happen if those who had control or management used proper care. 4. The absence of explanation by the defendant. a. Nature of the accident b. Control over the cause -Exclusivity is important because it norrows the point person for negligence Professional Services v. Agana G.R. No. 126297 January 31, 2007 - After her hysterectomy operation at Medical City, Natividad Agana found out that two pieces of sponges were left inside her, which has caused her pain for a long time. Dr. Ampil, who closed the incision, invoking res ipsa loquitur, blamed Dr. Fuentes, who conducted the operation itself. The SC absolved Dr. Fuentes, since he ceased to have control of the thing which caused the injury, when Dr. Ampil took over. On the contrary, Dr. Ampil was the lead surgeon, liable under the "captain of the ship" rule. - Doctrine: The most instrumental in the requisites [see Requisites above] for the doctrine to apply is the control and management of the thing which caused the injury. Josefa v. Manila Electric Co. G.R. No. 182705 July 18, 2014

-The present case satisfiesall the elements of res ipsa loquitur. It is very unusual and extraordinary for the truck to hit an electricity post, an immovable and stationary object, unless Bautista, who had the exclusive

management and control of the truck, acted with fault or negligence. We cannot also conclude that Meralco contributed to the injury since it safely and permanently installed the electricity post beside the street. Thus, in Republic v. Luzon Stevedoring Corp.,52 we imputed vicarious responsibility to Luzon Stevedoring Corp. whose barge rammed the bridge, also an immovable and stationary object. In that case, we found it highly unusual for the barge to hit the bridge which had adequate openings for the age of water craft unless Luzon Stevedoring Corp.’s employee had acted with negligence.

BJDC Construction v. Lanuzo G.R. No. 161151 March 24, 2014 Res ipsa loquitur is a Latin phrase that literally means "the thing or the transaction speaks for itself." It is a maxim for the rule that the fact of the occurrence of an injury, taken with the surrounding circumstances, may permit an inference or raise a presumption of negligence, or make out a plaintiff's prima facie case, and present a question of fact for defendant to meet with an explanation. Where the thing that caused the injury complained of is shown to be under the management of the defendant or his servants; and the accident, in the ordinary course of things, would not happen if those who had management or control used proper care, it affords reasonable evidence — in the absence of a sufficient, reasonable and logical explanation by defendant — that the accident arose from or was caused by the defendant's want of care. This rule is grounded on the superior logic of ordinary human experience, and it is on the basis of such experience or common knowledge that negligence may be deduced from the mere occurrence of the accident itself. Hence, the rule is applied in conjunction with the doctrine of common knowledge. For the doctrine to apply, the following requirements must be shown to exist, namely: (a) the accident is of a kind that ordinarily does not occur in the absence of someone’s negligence; (b) it is caused by an instrumentality within the exclusive control of the defendant or defendants; and (c) the possibility of contributing conduct that would make the plaintiff responsible is eliminated.

c. No contribution to the injury from the injured Note: this element perhaps makes a medical negligence case a prime candidate for the application of the rule because ordinarily, a patient is rendered incapable of acting while under the care of a doctor. 4. Effect of direct evidence Layugan v. IAC G.R. No. 73998 November 14, 1988 -

Hence, it has generally been held that the presumption of inference arising from the doctrine cannot be availed of, or is overcome, where plaintiff has knowledge and testifies or presents evidence as to the specific act of negligence which is the cause of the injury complained of or where there is direct evidence as to the precise cause of the accident and all the facts and circumstances attendant on the occurrence clearly appear. Finally, once the actual cause of injury is established beyond controversy, whether by the plaintiff or by the defendant, no presumptions will be involved and the doctrine becomes inapplicable when the circumstances have been so completely elucidated that no inference of defendant’s liability can reasonably be made, whatever the source of the evidence, as in this case.

Tan v. Jam Transit G.R. No. 183198 November 25, 2009 - Tan was the owner of a jitney loaded with quail eggs and duck eggs. It was negotiating a left turn when it collided with a JAM Transit bus. The jitney turned turtle. Its driver and enger were injured. The eggs were destroyed. SC held the bus driver was negligent for overtaking when there were double yellow center lines on the road, which means overtaking is prohibited. Res ipsa loquitur was held applicable, since the incident could not have happened in the absence of negligence, the bus was under the control of the driver, and the jitney driver was not contributorily negligent. - Doctrine: Res ipsa loquitur is not a rule of substantive law and does not constitute an independent or separate ground for liability. Instead, it is considered as merely evidentiary, a mode of proof, or a mere procedural convenience, since it

-

furnishes a substitute for, and relieves a plaintiff of, the burden of producing a specific proof of negligence. Notes: While the SC stated that the doctrine was applicable, it still examined the evidence proving the negligence of the bus driver. This means that the doctrine was not necessary in resolving the case.

College Assurance v. Belfranlt G.R. No. 155604 November 22, 2007 - Fire razed a building owned by Belfranlt Development and leased to College Assurance Plan. damages. It was caused by an overheated coffee percolator in the store room leased to College Assurance. College Assurance assailed the report of the fireman to this effect. The SC held that even without such report, res ipsa loquitur may be applied. The fire was not an spontaneous occurrence. It originated from the store room, in the possession and control of College Assurance. Belfranlt Development had no hand in the incident, and it has no means to find out for itself the cause of the fire. - Doctrine: When the doctrine applies, it may dispense with the expert testimony to sustain an allegation of negligence. The inference of negligence is not dispelled by mere denial. - Notes: The case illustrates clearly the element of control in the requisites for the application of the doctrine. Also, only College Assurance has the knowledge of, or at least it had the best opportunity to ascertain, the cause of the fire. 5. Nature of the rule The doctrine is not a rule of substantive law but merely a mode of proof or a mere procedural convenience. However, much has been said that res ipsa loquitur is not a rule of substantive law and, as such, does not create orconstitute an independent or separate ground of liability. Instead, it is considered as merely evidentiary or in the nature of a procedural rule. It is regarded as a mode of proof, or a mere procedural convenience. Nature of a procedural rule, a rule of evience and not a rule of substantive law and therefore does not create or constitute an independent or separate ground of liability. 6. Effect of the rule

The doctrine of res ipsa loquitur as a rule of evidence is peculiar to the law of negligence which recognizes that prima facie negligence may be established without direct proof and furnishes a substitute for specific proof of negligence. [Layugan v. IAC, 1988; Batiquin v. CA, 1998] The rule, when applicable to the facts and circumstances of a particular case, is not intended to and does not dispense with the requirement of proof of culpable negligence on the part of the party charged. It merely determines and regulates what shall be prima facie evidence thereof and facilitates the burden of plaintiff of proving a breach of the duty of due care. [Layugan v. IAC, 1988; Batiquin v. CA, 1996] [I]t furnishes a substitute for, and relieves a plaintiff of, the burden of producing specific proof of negligence.[Ramos v. CA, 1999; Tan v. JAM Transit, 2009] As stated earlier, the defendant’s negligence is presumed or inferred when the plaintiff establishes the requisites for the application of res ipsa loquitur. Once the plaintiff makes out a prima facie case of all the elements, the burden then shifts to defendant to explain. The presumption or inference may be rebutted or overcome by other evidence and, under appropriate circumstances disputable presumption, such as that of due care or innocence, may outweigh the inference. It is not for the defendant to explain or prove its defense to prevent the presumption or inference from arising. Evidence by the defendant of say, due care, comes into play only after the circumstances for the application of the doctrine has been established. [DM Consunji v. CA, 2001] 7. Justification for the rule DM Consunji v. CA G.R. No. 137873 April 20, 2001 -

One of the theoretical basis for the doctrine is its necessity, i.e., that necessary evidence is absent or not available. xxx The doctrine is based in part upon the theory that the defendant in charge of the instrumentality which causes the injury either knows the cause of the accident or has the best opportunity of ascertaining it and that the plaintiff has no such knowledge, and therefore is compelled to allege negligence in general and to rely upon the proof of the

happening of the accident in order to establish negligence. The inference which the doctrine permits is grounded upon the fact that the chief evidence of the true cause, whether culpable or innocent, is practically accessible to the defendant but inaccessible to the injured person. It has been said that the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur furnishes a bridge by which a plaintiff, without knowledge of the cause, reaches over to defendant who knows or should know the cause, for any explanation of care exercised by the defendant in respect of the matter of which the plaintiff complains. The res ipsa loquitur doctrine, another court has said, is a rule of necessity, in that it proceeds on the theory that under the peculiar circumstances in which the doctrine is applicable, it is within the power of the defendant to show that there was no negligence on his part, and direct proof of defendant’s negligence is beyond plaintiff’s power. 8. Res ipsa inquitor versus expert testimony in medical negligence cases Cruz v. CA G.R. No. 122445 November 18, 1997 Dr. Cruz performed a hysterectomy on Lydia Umali. The hospital was untidy, and during the operation, the family had to obtain blood, oxygen supply,and other articles necessary for the operation outside the hospital. Lydia went into shock and her blood pressure dropped. She was transferred to another hospital. Dr. Cruz was charged with reckless imprudence resulting to homicide. The SC absolved Dr. Cruz. While the facts point to the existence of reckless imprudence, it was not shown that such imprudence caused the death of Lydia. Moral and exemplary damages were, however, awarded. Doctrine: By accepting a case, a doctor in effect represents that, having the needed training and skill possessed by physicians and surgeons practicing in the same field, he will employ such training, care and skill in the treatment of his patients. He therefore has a duty to use at least the same level of care that any other reasonably competent doctor would use to treat a condition under the same circumstances. It is in this aspect of medical malpractice that expert testimony is essential to establish not only the standard of care of the profession but also that the physician's conduct in the treatment and care falls below such standard. Further, inasmuch as the causes of the injuries involved in malpractice actions are determinable only in the light of scientific knowledge, it has been recognized that expert testimony is usually necessary to the conclusion as to causation.

Casumpang v. Cortejo G.R. Nos.171127, 171217 & 171221 March 11, 2015 -

Once a physician-patient relationship is established, the legal duty of care follows. The doctor accordingly becomes duty-bound to use at least the same standard of care that a reasonably competent doctor would use to treat a medical condition under similar circumstances.

-

Medical malpractice suit, an action available to victims to redress a wrong committed by medical professionals who caused bodily harm to, or the death of, a patient.33 As the term is used, the suit is brought whenever a medical practitioner or health care provider fails to meet the standards demanded by his profession, or deviates from this standard, and causes injury to the patient.

-

To successfully pursue a medical malpractice suit, the plaintiff (in this case, the deceased patient’s heir) must prove that the doctor either failed to do what a reasonably prudent doctor would have done, or did what a reasonably prudent doctor would not have done; and the act or omission had caused injury to the patient.34 The patient’s heir/s bears the burden of proving his/her cause of action.

Borromeo v. Family Care Hospital, Inc. G.R. No. 191018 January 25, 2016 Res ipsa loquitur is not applicable when the failure to observe due care is not immediately apparent to the layman. The petitioner cannot invoke the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur to shift the burden of evidence onto the respondent. Res ipsa loquitur, literally, "the thing speaks for itself;" is a rule of evidence that presumes negligence from the very nature of the accident itself using common human knowledge or experience. The application of this rule requires: (1) that the accident was of a kind which does not ordinarily occur unless someone is negligent; (2) that the instrumentality or agency which caused the injury was under the

exclusive: control of the person charged with negligence; and (3) that the injury suffered must not have been due to any voluntary action or contribution from the injured person.38 The concurrence of these elements creates a presumption of negligence that, if unrebutted, overcomes the plaintiffs burden of proof. Cayao- Lasam v. Sps. Ramolete G.R. No. 159132 December 18, 2008 Dr. Cayao-Lasam conducted a dilatation and curettage procedure (raspa) on Ramolete. Almost a month after, she went back to the hospital. A dead fetus was found in her womb. She underwent operations, which rendered her incapable of bering a child. The SC absolved Dr. Cayao-Lasam, since there was no expert testimony presented to the effect that she breached her professional duties, and Ramolete herself failed to attend the followup check-ups after the operation, which could have avoided the injury. Doctrine: There are four elements involved in medical negligence cases: duty, breach, injury and proximate causation. A physician is duty-bound to use at least the same level of care that any reasonably competent doctor would use to treat a condition under the same circumstances. Breach of this duty, whereby the patient is injured in body or in health, constitutes actionable malpractice. As to this aspect of medical malpractice, the determination of the reasonable level of care and the breach thereof, expert testimony is essential. Notes: The elements enumerated is the same as that for a tort. It, therefore, shares the same problem as that of tort, that is, lack of statutory basis. The requirement of expert testimony is understandable in this case. Lucas v. Tuaño G.R. No. 178763 April 21, 2009 Lucas consulted Dr. Tuaño his "sore eyes." He was prescribed a medicine. Not long after, however, his sore eyes turned into a viral infection. Maxitrol was then prescribed. The infection subsided. Upon discovery that Maxitrol increased the chance of contracting glaucoma, he consulted Dr. Tuaño, who brushed it aside. His right eye became blind because of glaucoma. On consultation to another physician, Lucas was informed that his condition would require long-term care. The SC absolved Dr. Tuaño. It found that Lucas failed to discharge the burden of proof by failing to present expert testimony to establish the standard of care required, breach, and proximate causation, which requires expert testimony. Doctrine: Just like any other proceeding for damages, four essential elements i.e., (1) duty; (2) breach; (3) injury; and (4) proximate causation, must be established in medical negligence cases. In accepting a case, the physician, for all intents and purposes, represents that he has the needed training and skill possessed by physicians and surgeons

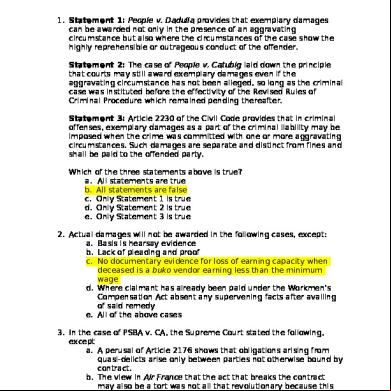

practicing in the same field; and that he will employ such training, care, and skill in the treatment of the patient. This standard level of care, skill and diligence is a matter best addressed by expert medical testimony, because the standard of care in a medical malpractice case is a matter peculiarly within the knowledge of experts in the field. Notes: The action was primarily based on Article 2176. However, instead of using the three elements for quasidelict, the elements of the commonlaw tort was used. Ramos v. CA G.R. No. 124354 December 29, 1999 - For her cholecystectomy, the surgeon for Ramos was late, and her anesthesiologist was incompetent. Something went wrong during the intubation, that her nailbeds became bluish. She had to be placed in a trendelenburg position, so her brain can get enough oxygen. A respiratory machine was rushed into the operating room. For lack of oxygen in her brain, she went into a comatose condition. In the action for damages, the SC held that the damage sustained presents a case for the application of res ipsa loquitur. Brain damage does not normally occur in a gall bladder operation in the absence of negligence. The anesthesia was under the exclusive control of the doctors. The patient was unconscious, incapable of contributory negligence. The presumption of negligence arose, and remained unrebutted. - Doctrine: The injury incurred by petitioner Erlinda does not normally happen absent any negligence in the istration of anesthesia and in the use of an endotracheal tube. The instruments used in the istration of anesthesia, including the endotracheal tube, were all under the exclusive control of Dr. Gutierrez and Dr. Hosaka. Thus the doctrine of res ipsa loquitor can be applied in this case. Res ipsa could apply in medical cases. In cases where it applies, expert testimony can be dispensed with. - Notes: Expert testimony may be dispensed with when res ipsa loquitur applies. There were proof of negligence in this case. Nonetheless, the doctrine was still applied. Cruz v. Agas, Jr. G.R. No. 204095 June 15, 2015 In this case, the Court agrees with Dr. Agas that his purported negligence in performing the colonoscopy on Dr. Cruz was not immediately apparent to a layman to justify the application of res ipsa loquitur doctrine.